State law forbids revenue’s ‘financial responsibility’ enforcement in defiance of its nature, numerous provisions

Hearing officer denies my bid to grill David Gerregano about his oppressive alliance with insurance industry against the traveling public, generating 25,000 criminal convictions yearly.

I have five days to answer the 15-page counterattack against my motion for temporary injunction to restore my tag in my fight to overturn the fourth-largest fraud operating in state of Tennessee. (Ask me later about frauds No.1 , 2 and 3.)

By David Tulis / NoogaRadio Network

Commissioner David Gerregano’s toehold in defending his TFRL program “is so precarious,” I state in my reply brief, “that he trusts in the twigs of legislative history to save policy from the abyss. The legislators he quotes want ‘more teeth’ in the law – they want compulsory insurance on all vehicles. But their updates of T.C.A 55-12-139 do little more than ink Halloween goblin incisors on the cheeks of the law.

“The department’s reply to petitioner’s motion for a temporary injunction defends his policy as against the wordy but clear provisions of the law, ones the commissioner disputes with a solipsistic treatise showing him far removed from ever-fixed statutory construction rules that see the legislature’s intentions not in speechmaking but in the incontestable oratory of black-letter law.”

What follows is what I believe is the key filing to sew up and have the administrative judge toss out (at least in his mind, pending the hearing and briefs) the position of the party he represents. He is the judge, and neutral. But he sits in the place of Cmsr. Gerregano in hearing this tax matter.

The case is taking place in a murky non-place in Tennessee law, in an administrative netherworld not permitted in state law. Only the department of safety holds hearings on “driving without insurance” cases. But because DOR has become an independent actor outside the law, it abuses people by revoking their tags administratively based on “probable cause” created by its continual search of insurance company databases. It has gone rogue. Because this entire program is against the law and illegal, it has no way of giving hearing BEFORE a revocation.

That’s a breach of due process. I point this defect out to Brad Buchanan, hearing officer. DOR does hold hearings under the UAPA,the uniform administrative procedures act, but under its own rules. Despite this prohibition, my case proceeds under the UAPA. The result of this exchange is that I “cure” the defect by continuing to pursue my case in agency. He had offered me the chance to dismiss my own case. Had I done so, who could have heard my grievance? Safety? No, safety is not the part that moved to revoke my tag.

Below is the first part of my 26pp reply to Camille Clline’s filing arguing against my injunction demand.

Likelihood of success & claims of pari materia

Respondent’s defense of his policy works if the law is rent apart and provisions are read decohered from the whole, his support primarily sect. 139 and Atwood exploited apart from the infrastructure of the law that DOR ignores as if it doesn’t exist.

The commissioner cites three provisions for authority to compel motorists to always have in their vehicle glove boxes a proof of financial responsibility:

See Tenn. Code Ann. § 55-12-139(a) (making compliance with financial responsibility requirements mandatory for “every vehicle subject to the registration and certificate of title provisions”);

Tenn. Code Ann. § 55-12-139(c)(1) (providing that failure to provide evidence of financial responsibility is a misdemeanor offense)[footnote omitted];

Tenn. Code Ann. § 55-12-210(a)-(c)(directing the Department to check vehicle registrations against insurance company records to verify that active liability insurance coverage is in place for vehicles operating on Tennessee roads, issue a series of notices to the registrant if coverage is unconfirmed, and ultimately suspend the registration if the registrant fails to cure noncompliance).

Response p. 3 (paragraphing added)

“Taken together,” DOR states, “these three provisions require registrants operating vehicles subject to registration on Tennessee roads to procure an adequate form of financial responsibility in advance of an encounter with law enforcement that would prompt an officer to request proof of financial responsibility,” and “the only way” for registrants to comply “is to carry the requisite proof in their vehicles.”

The omitted duty of commissioner in this conflict is to see the law as a whole, and not to atomize provisions that appear on the surface to authorize respondent’s sweeping authority. DOR states in response p. 3, footnote No. 1, that sect. 139(a) provides that “this part shall apply to every vehicle subject to the registration and certificate of title provisions.”

In virtuous admission, DOR goes on, “The ‘part’ referenced in subsection (a) is Title 55, Chapter 12, Part 1, where the TFRL is codified and financial responsibility requirements are set forth.”

But “Part 1” contains requirements for financial responsibility following an accident. T.C.A. § 55-12-139 must work pari materia with the rest of the law — with Part 1 — that creates legal duty to show financial responsibility only following a qualifying accident or judgment. Does T.C.A. § 55-12-139 define financial responsibility? It does at (b)(2). For the purposes of this section, “financial responsibility” means:

(b)(2)(B) A certificate, valid for one (1) year, issued by the commissioner of safety, stating that: (i)A cash deposit or bond in the amount required by this part has been paid or filed with the commissioner of revenue (emphasis added)

The legislators didn’t limit cash deposit or bond to T.C.A. § 55-12-102(12) et seq. The “part” includes § 55-12-105(b)(2) and (3) the deposit of cash or the filing of a bond in the total amount of all damages suffered — the amount determined after an accident, T.C.A. § 55-12-110.

T.C.A. § 55-12-139 cannot mean financial responsibility is required at all times, when the very definition can be satisfied, as defined in sect. 139, with a cash deposit or bond after an accident. By respondent’s footnote in concession, sect. 139 must be used in conjunction with the entirety of Part 1. (1)

Part 1 is after-accident legislation, as Burress v. Sanders, 31 S.W.3d 259, 262, 263 (Tenn. Ct. App. 2000) and other cases explain.

DOR uses a provision regarding a law enforcement officer at an accident scene or transportation enforcement “traffic stop” to serve the state interest in financial responsibility set forth in TFRL. “In case of an accident for which notice is required under § 55-10-106, the officer shall request evidence of financial responsibility from all drivers involved in the accident without regard to apparent or actual fault” T.C.A. § 55-12-139.

The sum of petitioner’s response is that the duty imposed on an officer to ask questions applies only “as required” upon a party who, when stopped, is under the authority of TFRL because of an earlier accident or court judgment as a condition of the retention of a license which may require SR-22 high-risk insurance.

Support David with F$5 gift today

Respondent reads the phrase “as required by this section” as meaning that evidence of financial responsibility is required at all times.

Petitioner reads “as required by this section” to mean that one cannot avoid giving evidence of financial responsibility if one is liable under TFRL. Sect. 139 does not establish on its own a duty to have evidence of financial responsibility or financial security. The phrase is superfluous if financial responsibility is required by all at all times, as DOR says. “Every word in a statute ‘is presumed to have meaning and purpose, and should be given full effect if so doing does not violate the obvious intention of the Legislature’” Waters v. Farr, 291 S.W.3d 873, 881 (Tenn. 2009) (internal citation omitted). Petitioner reasonably reads the phrase “as required by this section” as supportive of his thesis that when an officer (crash scene, “traffic stop”) is required to ask for proof of financial responsibility, the vehicle registrant must give that proof because he or she is subject to the law as result of an earlier qualifying accident or a court judgment. Subsection (b)(1) does not require financial responsibility; it only tells the officer to request as required. How is financial responsibility required “pursuant” to this section? Answer: After a citation “as required by this section” or following an accident which requires an officer to request in this section. Petitioner doesn’t meet either criteria.

DOR runs its “mandatory insurance” project in defiance of the Atwood law savings clause that prohibits its misuse. According to DOR,

“[T]he Atwood Law does not limit its own application to vehicles involved in an accident.” Section 210(a)(1) “directs the Department to initiate its notice procedures ‘if there is evidence … that a motor vehicle is not insured” (emphasis added). If the General Assembly had intended to limit the Department’s administration of the Atwood Law to vehicles involved in an accident and thus implicated” under § 55-12-105(a), “it could easily have done so. However, the lack of any qualifying or narrowing language leaves the EIVS inquiry open to any motor vehicle registered in Tennessee.”

Response pp. 5, 6 (emphasis in original)

Respondent claims, in this admission, it can run EIVS without any filter to snag any registrant who is not an insurance company customer. Petitioner’s understanding is that TFRL Part 1 (the longstanding original law described by the courts) is “qualifying and narrowing language,” and Atwood in Part 2 secures the pre-existing scope of the financial responsibility law, as “Nothing in this part shall alter the existing financial responsibility requirements in this chapter” T.C.A. § 55-12-214.

A second limiting factor ignored by respondent, that its purpose is to “verify whether the financial responsibility requirements of this chapter have been met with a motor vehicle liability insurance policy” § 55-12-202. Purpose. Atwood is for verification only, and only as required for financial responsibility, which still means the same as in Part 1 and is only required after an accident or judgment.

A third limit is § 55-12-210 (a)(1)(B) concerning exemptions under this chapter. The only exemption or exception mentioned in chapter 12, TFRL of 1977, is at § 55-12-106 about revocation following an accident. Part 2 (Atwood) is not activated until required by conditions imposed under Part 1.

This response is not the place to detail the rules of statutory construction as they must control in this case. The rules are laid out in numerous cases. (2) DOR is keen to show the law is tougher now than before sect. 139 was updated, and wants legislative quotations and historical artifacts to control the meaning of the law, especially where complexity of provision may reign, but not ambiguity. (3) Legislators in 2002 wanted to make enforcement mandatory on people who haven’t had an accident. Legislators in 2002 and in 2015 verbally declare intentions, desires and understanding about the law, hoping to “[put] some teeth into the law” and, evidently, to make motor vehicle insurance policies a prerequisite for anyone to get on the road, whether car or motor vehicle.

Tulis motion temporary injunction Tulis v. DOR

DOR’s quotes from state Rep. William Lamberth, response p. 6, indicates that in 2015, 23 percent of vehicle registrants refuse motor vehicle insurance, and he points out “We have law that says you have to have financial responsibility.” But DOR fails to acknowledge what financial responsibility is. State Rep. William Lamberth is right, Tennessee has such a law — as laid out initially in 1949 and updated in 1977 — captured in what is now TFRL Part 1, successfully operating – as far as DOR is concerned – in an after-crash manner prior to Atwood. A legislator’s understanding or misunderstanding of existing law does not control how the actual black letter is administered. This member of Tennessee’s house of commons believes that because the law doesn’t cover 100 percent of vehicle registrants, it is “broken”; but that doesn’t mean Rep. Lamberth is right when he says, “This [amendment] fixes that.” His desires, opinions and expression of belief don’t control, nor allow the hearing officer to use legislative directional cues or wishful thinking by someone who may never have studied TRFL to wash away general assembly infrastructure at T.C.A. § 55-12-101 et seq, described by the courts repeatedly as a financial responsibility law in a voluntary insurance “after-accident state,” as noted in Erwin v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 232 F. Supp. 530, 533 (E.D. Tenn. 1964).

TFRL is wordy and complex, requiring study. But it’s not ambiguous if read correctly. It is constitutional — if properly administered.

State Rep. Randy Rinks (response p. 9), like others in the public, misunderstand the law as written, saying a 2001 effort to amend “puts some teeth into that [1977] law. Requires that whoever is going to be driving motor vehicles [to] have financial responsibility” (response p. 9).

Rep. Rinks’ hoped-for changes add teeth to the law concerning people who don’t comply with TFRL post-accident financial responsibility requirements. In the upper house, Sen. Jim Tracy (response p. 10) says in the 2005 debates on TFRL that “all vehicles driven on the public highways are subject to the mandatory financial responsibility law” and that the senate bill in question focuses on relief over forklifts, backhoes and perhaps hauling trailers. Department of safety (DOSHS) official Roger Hutto also appears as a DOR authority. He says “the current law says every vehicle is subject to the financial responsibility laws.” Messrs. Rinks, Tracy and Hutto make statements about mandatory financial responsibility — and they’re not wrong about its being mandatory.

It is mandatory on parties subject to it after a qualifying crash at §§ 55-12-104 and 105, and applicants for a driver license are required at § 55-12-138, certificates and certification, to agree to comply with it before any accident as a future potential liability.

Petitioner is not aware of any other law touching on a privilege that solicits and obtains such promise. (5)

The three ways of showing financial responsibility are proof of insurance, a cash deposit to the DOSHS commissioner or a surety bond certificate following an accident, per § 55-12-105 et seq. The definitions in sect. 102 don’t include affidavit, but affidavit by parties in a qualifying crash declaring they have reached a private arrangement are also proof of financial responsibility.

The commissioner’s policy is based on three general statements in sect. 139. The legislature’s “intent in enacting Tenn. Code Ann. § 55-12-139 is made abundantly clear by the original language of subsection (a): ‘Every vehicle driven on the highways of this state must be in compliance with the financial responsibility law’ (the ‘2002 Language’). 2001 Pub. Ch. 292, Section 1 (emphasis added)” (response p. 9) (emphasis in original).

The statement that “every vehicle driven *** must be in compliance” with TFRL is, in the context of TFRL, not an extension of the law to new parties, but reiteration of its main premise in Part 1. Those in a qualifying accident or judgment and subject to those provisions of law “must be in compliance with the financial responsibility law,” as the law states since 2002. (6) Even persons not in an accident or under judgment must be in compliance with TFRL. (7) But compliance means reporting after an accident and then procuring proof of financial responsibility as required.

The commissioner makes much of the attorney general opinion of 2003, response pp. 9, 10. Opinions of attorneys general and staff employees of the safety department (Roger Hutto) do not have authority to create programs, projects or legislation on their own. See Beazley v. Armour, 420 F. Supp. 503, 509 (M.D. Tenn. 1976), cited already. The hearing officer is asked to review this opinion in which the attorney general says changes in sect. 139 “significantly altered” TFRL, with the department of safety launching mandatory insurance policy ultra vires, a possibility outside the scope of this lawsuit.

Summary of how the law works

➤ T.C.A. § 55-12-210 gives revenue authority to “verify” insurance when used as proof of financial responsibility. The Tennessee Financial Responsibility Law of 1977 works today the same as it did in 1977 — and previously, judging by court rulings. Under T.C.A. § 55-12-210(a)(1), “the owner has thirty (30) days from the date of the notice to provide to the department of revenue: (A) The owner or operator’s proof of financial security *** .” Pursuant to sect. 1 of TFRL, “security” is required following an accident. See sects. 105 to 110 and sect. 112. Whatever DOR might claim, sect. 139 does not alter this arrangement of the parts, with department of safety in the lead role, giving revocation notices to revenue.

➤ T.C.A. § 55-12-139 amendments do not change the TFRL. Updates only add “teeth” to its enforcement by giving officers permission to request evidence of financial responsibility (defined in 1977) as (or, when) required. See T.C.A. § 55-12-119, “Proof of financial responsibility, when required under this chapter *** ” (emphasis added). Financial responsibility isn’t required until a qualifying accident or judgment in the Volunteer State.

➤ The department of safety decides when a person is under a duty to be financially responsible or secure. Safety decides when that responsibility ends. As a condition of reinstatement of a license, that requirement may last 3 years. Then the person is released. See sect.126. DOS keeps a record of the persons under the requirement. It is the DOR’s job to verify financial responsibility of only those under the requirement, using the statutory filter with aid of EIVS. Those released from the requirement should be filtered out. That is why Atwood is a verification program and not a program to check insurance status. See T.C.A. § 55-12-202 et seq. There is a difference between verification and a status check upon those behind a steering wheel.

General assembly rejects mandatory insurance

As stated by respondent p. 9 in footnote No. 11, “When courts are called upon to construe a statute, their goal is to give full effect to the General Assembly’s purpose, stopping just short of exceeding its intended scope”). The external sources to which a court may look for assistance in ascertaining the intent of the General Assembly include “the broader statutory scheme, the history and purpose of the legislation, public policy, historical facts preceding or contemporaneous with the enactment of the statute, and legislative history.” Citing the rules of construction is a danger for respondent as he rejects them, just as citing legislative history is a dodge pretending that sect. 139 is unclear.

Atwood’s purpose in sect. 202 is “to verify whether the financial responsibility requirements of this chapter have been met with a motor vehicle liability insurance policy.” Again, this is for verification only. The purpose of TFRL of 1977 is the requirement after an accident or judgment, the law’s history noted by the courts.

TFRL has not been revamped. It has not been repealed.

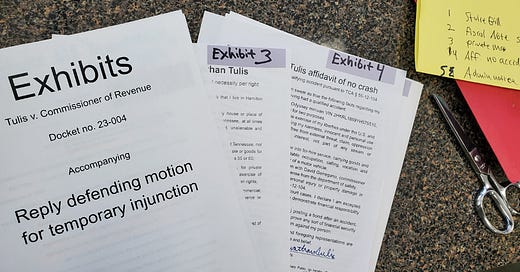

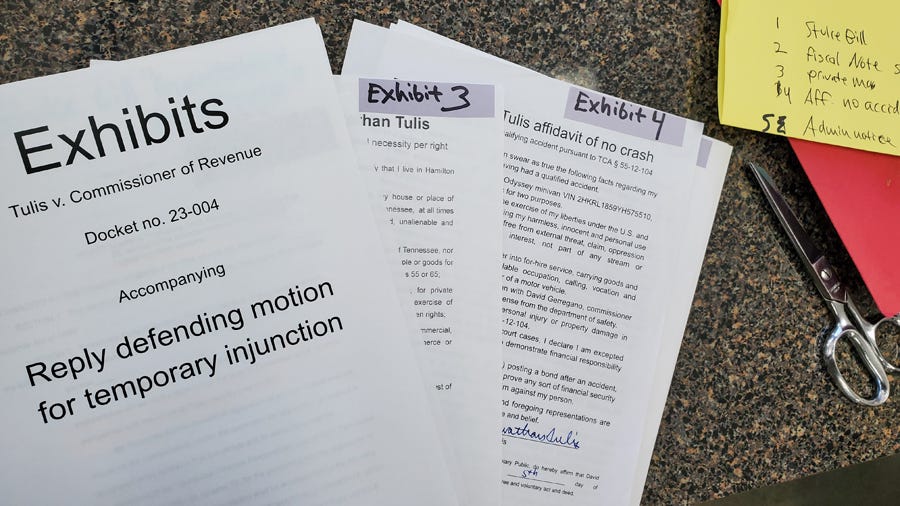

Efforts to make Tennessee a compulsory insurance state fail under House bill No. 244, filed Feb. 4, 1999, by petitioner’s former house representative, Arnold Stulce of Soddy-Daisy. The bill is titled “Mandatory Motor Vehicle Insurance Act of 1999.” EXHIBIT No. 1, Stulce 1999 mandatory insurance bill. EXHIBIT No. 2, Stulce bill fiscal note with summary.

It proposes no deletions in existing law, but to add three pages as chapter 4. Because it doesn’t take the axe to stale or marooned provisions in chapter 1 it would have added to the confusion, muddle and complexity, failing to establish clear, unambiguous law free of self-contradiction as created by respondent’s use of law. Petitioner suspects that if Tennessee is going to become a mandatory insurance state by law, it will have to scrap the existing statute as surplusage and start over with a decomplexified piece of privilege management legislation, clean, minimalist, and straightforward.

What we have before us, throughout Part 1, are evidences against DOR’s practices that the rules of statutory construction decry.

DOR denies TFLR parts fit together

Statute contradicts DOR policy, as marooned duties or now-needless provisions show.

➤ TCA 55-12-104(4) states, “The submission to the commissioner of notarized releases executed by all parties who had previously filed claims with the department as a result of the accident.” This provision envisions the parties’ having no insurance and in compliance with the law.

➤ Gerregano policy that all vehicle owners must continuously maintain insurance to use the public roads — absent a qualifying crash — contradicts the law. The commissioner of safety terminates a duty that a motorist show financial responsibility following a qualifying crash and suspension action by that department.

At any time after five (5) years from the date of revocation, the department of safety may, in its own discretion, or upon request of the person required to furnish proof of financial responsibility, release the requirement of that proof, if the records of the department of safety establish that the person, during the preceding five-year period, has not been convicted of any offense authorizing or requiring the suspension or revocation of a license or registration by the department of safety or by the department of revenue, and has not suffered suspension, revocation, prohibition, or cancellation of license as ordered by the department of safety or by a court.

55-12-102(d) (emphasis added)

➤ Sect. 126 provides a three-year maximum on the obligation of a person under sanction by department of safety to keep an insurance policy (SR-22).

(a) Except for suspensions under § 55-12-115, and the proof required prior to the issuance of a restricted license as provided in § 55-12-114, where a person is required to give proof of financial responsibility, the proof shall be maintained for a period of three (3) years by that person.

55-12-126. Maintenance of proof; suspension of license and registration

The first day after the third year ends, such owner can use the vehicle without insurance, just as he had been able before the wreck to go without a policy.

➤ In section § 55-12-110, on bonds and security, the bond amount is set at the limit of damages incurred in a qualifying accident. “(b) In no case shall security be required that is greater in amount than that specified in § 55-12-102, and in no event shall this security be in an amount less than five hundred dollars ($500).”

➤ No law exists telling the commissioner of safety what to do with $65,000 deposit paid before accident as the commissioner proposes in pre-hearing discussions. Deposits paid him after an accident go to the state treasury at § 55-12-112, where the funds are disbursed to cover accident costs. If the general assembly envisions requiring $65,000 cash deposit to be prospectively sent to the commissioner of safety or surety bonds purchased and the certificate mailed to the commissioner of safety, such a promise as required of driver license applicants § 55-12-138 would serve no purpose. DOR renders such provisions null.

➤ In § 55-12-114, the law contradicts agency policy as to whom must prove “financial responsibility.” First off, there must be a qualifying accident or judicial conviction of the driver or owner/operator. The law stipulates a three-year window requiring proof of financial responsibility. (8) That’s 3 x 365 days, or 1,095 days the party must be able to show proof. Twenty-four hours later, on day 1,096, such person is under no obligation to have liability coverage and proof thereof. The law grants release from an insurance requirement. If insurance were compulsory, three-year limits are no longer the law.

➤ If petitioner has an accident just outside the revenue department’s office tower with the hearing officer and causes $2,000 in damage, petitioner sends a $2,000 check to the commissioner of safety satisfying his obligation under sect. 105, deposit of security; proof of security. No further proof of financial responsibility is required from either petitioner nor the administrative judge. If in leaving Nashville petitioner is pulled over by a Davidson County deputy sheriff, and the deputy demands proof of financial responsibility, the check petitioner paid to safety Cmsr. Jeff Long is proof of financial responsibility, and no further proof of financial responsibility is required until a future accident.

➤ A person sends the commissioner $65,000 to use his car, per DOR’s theory of the law, and he has an accident costing him $5,000. He is at fault. After final judgment, the amount is paid from those funds. See § 55-12-112. Deposits. Does he have to send the commissioner 5,000 to bring up the fund balance to $65,000? He could have chosen instead to follow § 55-12-104 and 105 — and meet financial responsibility after an accident with the amount of damages incurred. Or does the commissioner refund the deposit? Policy leaves many unanswered questions, and requires numerous workarounds, field fixes and private/arbitrary policies and customs with no lawful basis or origin. Petitioner objects.

➤ What does the safety commissioner do with the money sent him under sect. 105 with which to pay a damaged party in a qualifying accident?

(a) Any money deposited with the commissioner [safety] in compliance with the requirements of this chapter shall be deposited by the commissioner in the custody of the state treasurer, and shall be applicable only to the payment of a judgment or judgments rendered against the person making the deposit or the person in whose behalf the deposit was made. The commissioner is authorized to pay out of any funds deposited in compliance with the requirements of this chapter, the amount of any final judgment returned against the party making the deposit or the person in whose behalf the deposit was made, upon receipt of a certified copy of the final judgment.

(b) After expiration of one (1) year from the date of the accident for which deposit has been made, the commissioner shall, upon receipt of a sworn statement of the party making the deposit that no court action has been brought as a result of the accident for which the deposit was made, return the deposit to the person making the deposit. Should the commissioner have reason to believe that this sworn statement is not true, additional proof may be required to substantiate the statement as the commissioner considers necessary.

55-12-112. Deposits.

The $65,000 deposit to the commissioner of safety is paid by a qualifying accident party to cover damage. The law does not envision $65,000 pre-payments to use the public roads in Tennessee.

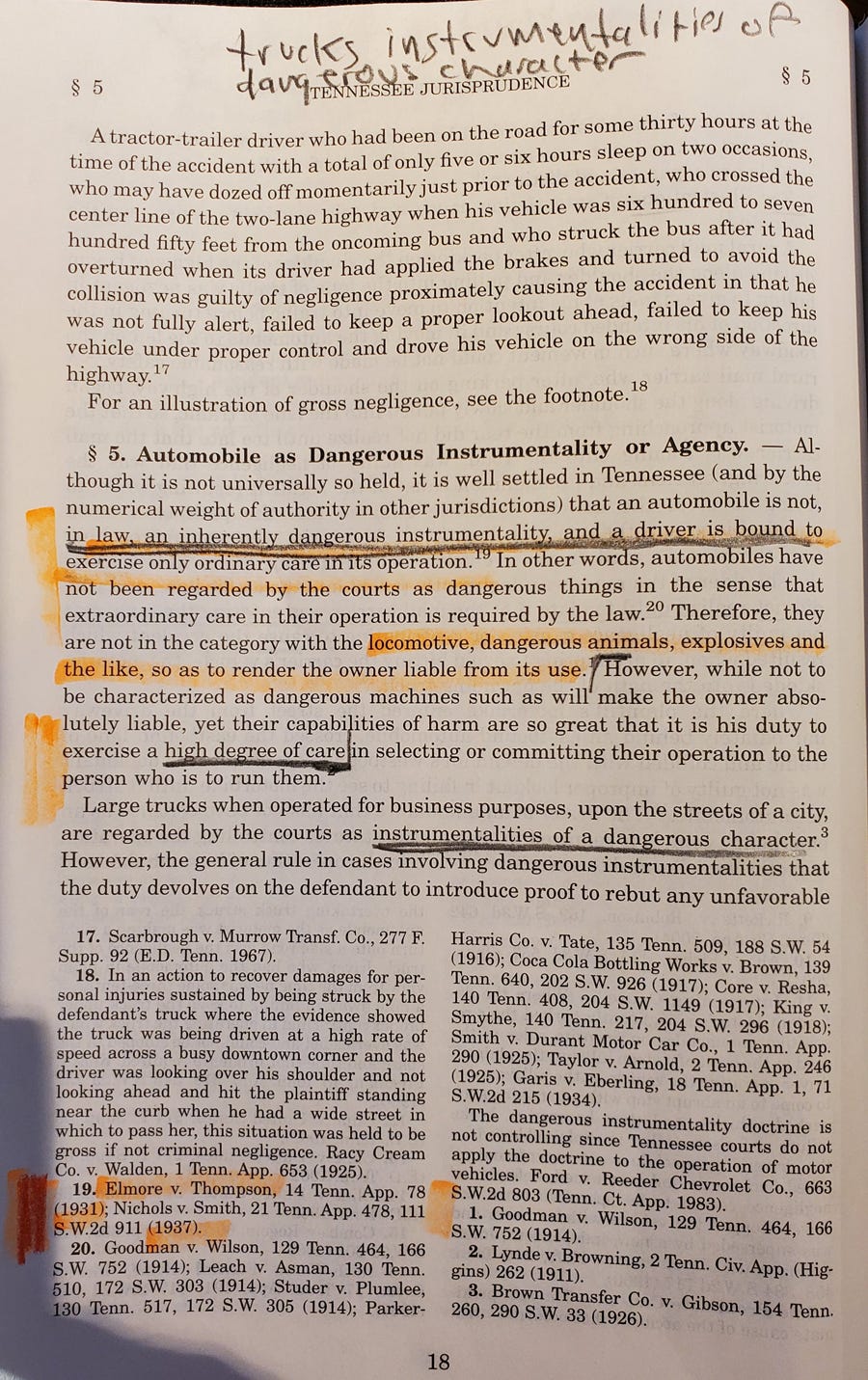

DOR alleges my being on the road without a tag or with a temporary tag without insurance is “inherently dangerous.” This position is nonsense as autos are not deemed inherently dangerous under use of ordinary care. (Photo David Tulis of page in TennJur)

Harm to respondent or public interest?

In rebutting petitioner’s analysis of irreparable harm, the commissioner avers petitioner faces no imminent irreparable harm if “he operates his vehicle without a valid registration” or “elects to drive on a suspended registration.” The commissioner says petitioner “poses a substantial risk of harm to the public” and that the use of his car — which is the issue, automobile, not operating a motor vehicle — is an “inherently dangerous activity” (response p. 13).

Such statements are lawyerly misdirection against the justice interest of the administrative judge. Petitioner is not “operating” a “motor vehicle” – because the minivan is not a motor vehicle any longer by function of state law, having been removed from the registered motor vehicle rolls. It is in an Adam’s costume, unadorned – it’s simply an automobile, a conveyance machine or instrument. Its use is limited to private purposes – not commerce. The car is not dangerous, and petitioner’s not having insurance is not dangerous, because the law allows it. The commissioner hyperventilates that petitioner is a danger to society, a threat to the public in the minivan’s during its use on the roads. For the petitioner to get a tag provisionally — without his having insurance — is not a danger to the public. Insurance in no way makes use of a car less dangerous. It depends on the person behind the wheel.

Automobiles are not inherently dangerous. “Although it is not universally so held, it is well settled in this State (and by the numerical weight of authority in other jurisdictions), that an automobile is not, in law, an inherently dangerous instrumentality, and a driver is bound to exercise only ordinary care in its operation, or that degree of care or caution which an ordinarily careful and prudent person would exercise under the same circumstances.” Elmore v. Thompson, 14 Tenn. App. 78 (1931). “This is not a case of a master confiding to his servant’s use a dangerous instrumentality, which furnishes ground of liability, independent of the ordinary rules of respondeat superior. These dangerous instrumentalities are such as poisons, high explosives, spring guns, and the like. Railway locomotives with steam up, out upon the track, have frequently been so designated, but not an automobile. Even where the instrumentality is inherently dangerous, while some cases treat the liability as absolute, a greater number of authorities regard it as a situation wherein a high degree of care is required, but not imposing liability for a willful or wanton act such as playing pranks and practical jokes with the thing in question by the servant to whom it was confided. Mechem, Outlines of Agency, § 543, pp. 361, 362.” Terrett v. Wray, 171 Tenn. 448, 105 S.W.2d 93, 94 (1937). “[T]he weight of authority is that an automobile is not a dangerous instrument, so as to be classed with locomotive engines, dangerous animals, explosives” Goodman v. Wilson, 129 Tenn. 464, 166 S.W. 752, 753 (1914). See Tennessee Jurisprudence, Automobiles, § 5, Automobile as Dangerous Instrumentality or Agency (2007 edition).

DOR’s response shows prejudice and bad faith because the commissioner ignores the petitioner’s stated claims for demanding protection of his rights of ingress and egress, aka free communication on the public right of way, or pleasure travel.

The commissioner in making this claim knowingly and intentionally is denying petitioner enjoyment of rights of ingress and egress from the soil upon which he abides in Soddy-Daisy. He is announcing he is co-operator with others to oppress petitioner’s constitutionally guaranteed rights, as spelled out in State v. Booher, 978 S.W.2d 953, 955–56 (Tenn. Crim. App. 1997), Tulis motion p. 9, and many cases cited in Tennessee transportation administrative notice, of record. EXHIBIT No. 3, Affidavit on status as private man, acting under personal necessity per right.

He claims authority to surveil every motorist on the road with his all-seeing EIVS “eye of Sauron” and to make that person subject to the cop and deputy. But the commissioner closes his lids and pretermits the rights of free passage on the public right of way of people such as petitioner, pretending such liberties don’t exist. He pretermits also the dispositive fact that safe-driving petitioner has had no accident. The state tax chief is alleging a public safety police power exercise claim without warrant or nonfraudulent lawful basis and evidences evil motive in abusing protected and protectible state and federal rights.

The judge calls himself a stickler for details and proper judicial form. So is petitioner — a person of exacting nature, ready to be wildly free and joyous on a right occasion, but ready to comply with any law that applies to him to the very edge of that law’s authority. As he insists in his motion, pp. 4ff, petitioner necessarily uses his minivan solely for enjoyment of ingress and egress rights, in the use of the van for pleasure purpose, private vocation or personal or family necessity, and in the exercise of protected rights of assembly, religion, press and more. He is suing to get back the use of the car as a motor vehicle. Right now, he cannot use it as a motor vehicle, either lawfully nor legally under statute. He does not intend to. The motor vehicle status is part of privilege, denied him by revocation.

The issue in the motion for temporary injunction is his use pending restoration of his tag. It is his use of the car for commerce as a motor vehicle, separate from private use that remains not implicated as a matter of law. Unless DOR admits that an automobile may be used upon the highways without being registered as a motor vehicle, petitioner suffers the loss of property and its use because of abuse by police, deputies and troopers obeying department policy. (9)

The commissioner’s response is first indication of his position on TFRL. It also signals his rejection of conflict in the larger context of ingress/egress rights in general and the subcategory of taxable transportation or regulable vehicular commerce under Title 55 privilege. He appears willing to oppress petitioner conjoined with others in predicate acts using the U.S. mails and in knowing and intentional deeds under color of law, to injure petitioner in constitutionally guaranteed, God-given inherent and unalienable rights of ingress and egress from the soil in the state of Tennessee whereat he abides.

The short form of petitioner’s defense of TFRA is that sect. 210 describes how revenue authority operates upon a registrant with notices, for purpose of administering 202 (“to verify whether the financial responsibility requirements of this chapter have been met” (emphasis added) upon motor vehicle owners or drivers described in the chapter at sects. 104 and 105 (accident reports, and deposit of security; proof of security).

If a motor vehicle were inherently dangerous, DOR would not allow people to continue to operate their vehicles 30 day after their policies lapse under notice pursuant to sect.110? Travelers complying with the law and using their motor vehicles with proper lookout and reasonable care are, the commissioner says, “inherently dangerous” and are presumed negligent if they don’t carry insurance. His characterizations are incredible and unreasonable. DOR may say they allow 30 days because they are unable to verify your insurance or an exemption. The means are to include NAIC number, policy number and other elements. § 55-12-205 & 207. The exemptions are under 55-12-106 as mentioned earlier, after an accident. The Atwood program requires the involvement of the dept of safety. 55-12-204. DOSHS is meant to filter the persons required to have POFR or an exemption.

Footnotes

The highlighted portion of sect. 139 of interest is at bottom, in blue type. TCA 139(b)(1)(C) If the driver of a motor vehicle fails to show an officer evidence of financial responsibility, or provides the officer with evidence of a motor vehicle liability policy as evidence of financial responsibility, the officer shall utilize the vehicle insurance verification program as defined in § 55-12-203 and may rely on the information provided by the vehicle insurance verification program, for the purpose of verifying evidence of liability insurance coverage.(2) For the purposes of this section, “financial responsibility” means:(A) Documentation, such as the declaration page of an insurance policy, an insurance binder, or an insurance card from an insurance company authorized to do business in this state, whether in paper or electronic format, stating that a policy of insurance meeting the requirements of this part has been issued;(B) A certificate, valid for one (1) year, issued by the commissioner of safety, stating that:(i) A cash deposit or bond in the amount required by this part has been paid or filed with the commissioner of revenue; or2.Petitioner reserves the right to go into detail on statutory construction in his brief, citing cases such as these that serve petitioner’s defense of the law. State v. Smith, 495 S.W.3d 271, 273–74 (Tenn. Crim. App. 2016); State v. Grosvenor, 149 Tenn. 158, 258 S.W. 140 (1924); Waters v. Farr, 291 S.W.3d 873, 881 (Tenn. 2009); Doe v. Roe, 638 S.W.3d 614, 617–18 (Tenn. Ct. App. 2021); Neff v. Cherokee Ins. Co., 704 S.W.2d 1, 2–3 (Tenn. 1986); Pryor v. Marion Cnty., 140 Tenn. 399, 204 S.W. 1152, 1154 (1918); Sw. Williamson Cty. Cmty. Ass’n v. Saltsman, 66 S.W.3d 872, 881 (Tenn. Ct. App. 2001)33.See Scalia, Antonin, & Bryan A. Garner. Reading Law; The Interpretation of Legal Texts (St. Paul, MN: Thomson/West, 2012). 561pp.

Among doctrines of statutory construction in view in this case are canon No. 26. Surplusage Canon. If possible, every word and every provision is to be given effect (verba cum effectu sunt accipienda). None should be ignored. None should needlessly be given an interpretation that causes it to duplicate another provision or to have no consequence. Canon No. 27. Harmonious-Reading Canon. The provisions of a text should be interpreted in a way that renders them compatible, not contradictory. Canon No. 28. General/Specific Canon. If there is a conflict between a general provision and a specific provision, the specific provision prevails (generalia specialibus non derogant).

5.The commissioner of safety includes a brief summary of TFRL on driver license applications under chapter 50 and at § 55-12-138 asks applicant to agree with the law should it come to apply to him.

The teenager or other driver license applicant avers,

I CERTIFY THAT I UNDERSTAND ABOUT TENNESSEE’S FINANCIAL RESPONSIBILITY LAW AND I AGREE TO ABIDE BY IT.

Only a law with a possible future claim upon a driver or operator requires such certification — because TFRL creates no duty to act on anyone who hasn’t had a qualifying crash per T.C.A. § 55-12-105.

6.

State law requires drivers to keep a logbook.

Each driver shall maintain, and keep current, a daily log book detailing the hours worked. The log book for the past thirty (30) working days must be in the driver’s possession at all times when on duty. The log book shall be made available for inspection upon the request of any law enforcement officer or passenger

Tenn. Code Ann. § 55-20-204

The broad and general statement “[e]ach driver” creates no duty on 100 percent of drivers in Tennessee, such as petitioner. Under the rule of reason and statutory construction, it applies to those people subject to and liable for performance under chapter 20, the passenger contract carrier safety act. General statements are bound by narrow precedent language in chapter 20 no less than in chapter 12.

7.

Petitioner is in compliance with the statute through certification of his driver license. But no accident compels action by petitioner under the law.

8.

(c) When the person’s license or registrations or both license and registrations are restored after suspension or revocation, the person shall give and shall maintain for three (3) years proof of financial responsibility as required by § 55-12-126, pay a one hundred-dollar restoration fee and pass the driver license examination as a condition precedent to the restoration of the license.

9.

‘Property has been well defined in Spann v. Dallas, 111 Tex. 350, 235 S.W. 513, 514, 19 A.L.R. 1387, as follows:

“Property in a thing consists not merely in its ownership and possession, but in the unrestricted right of use, enjoyment and disposal. Anything which destroys any of these elements of property, to that extent destroys the property itself. The substantial value of property lies in its use. If the right of use be denied, the value of the property is annihilated and ownership is rendered a barren right.’

A right to conduct a business, together with the incidental right to the good will thereof, is property.

‘The right to use one’s property in a lawful manner is within the protection of subdivision (1) of the 14th Amendment of the Constitution of the United States and Article I, Sec. 13 of the Idaho Constitution providing that no person shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. State v. Kouni, 58 Idaho 493, 76 P.2d 917.’ 69 Idaho 42-43, 202 P.2d 404.

Winther v. Vill. of Weippe, 91 Idaho 798, 803, 430 P.2d 689, 694 (1967) (internal citations omitted)