Rejection of law – not staff, not inmates – make jail evil place

Enslaved 6 hours is a harm, but is sanctifying because in personal dealings are glimpses of redemption at Silverdale detention center in Chattanooga

CHATTANOOGA, Tenn., Monday, Nov. 27, 2023— The people I meet in the Hamilton County jail are the sweet part of God’s blessings upon me, even in the adversity of false imprisonment and false arrest.

By David Tulis / NoogaRadio Network

I am denied enjoyment of many God-given and constitutionally guaranteed liberties by my jailing over a functional but damaged taillight, taken to the concertina-wire rimmed jail compound in eastern Chattanooga. But the legal harm intended by Austin Garrett, sheriff, and deputy Bennett is mitigated by encounters with hard-faced people doing their jobs and broken, fed-up souls lying on the floor in holding cells, awaiting word from family or bondsmen.

I spend six hours in custody Nov. 22, the day before Thanksgiving, seized out of my car before dawn that Wednesday enroute to NoogaRadio Network’s studio. Rightly, I am not put into the jail, but am in a “holding area.” Among the denizens:

➤ Mr. Eldridge, in orange jumpsuit and crocks, studiously sweeps the floor behind me as I stand at a counter being prepped for liberation. I approach, tell him he reminds me of the Genesis 39 account of Joseph in the prison. “Sir, I noticed in how careful you are in cleaning this place. You know that you are making it prosper, just as Joseph made the prison into which Potiphar’s wife threw him by false accusation.”

He is touched by the reference. “Yes, I know all about Joseph from the Word.”

“Everything that Joseph did he prospered, whether it was Potiphar’s house and all that he did, Potiphar didn’t know about anything but the food he put in his mouth and about his wife. Everything else he left to Joseph as his steward and Joseph made him prosper. In the prison, he also prospered and the place could not be run without him. Sir, do you know what it was that made him so valuable? He noticed things and took care of things as if they were his personal property and as if he was serving God himself.”

“My name is Eldridge.”

I tell him I am in the radio business and he ought to listening to me 7 a.m. in the morning at 96.9 FM. “96.9 FM,” he says, trying to remember, as if they were an incantation. “96.9.” I use his name two more times, trying to lodge it in my mind.

➤ The room is dusty. I point out to deputy Mrs. Roberts, taking my mugshot, that it seems impossible the camera can work, given the millimeter of dust atop it. She publishes a picture of me, in the jail lineup, in the middle of telling her about the dust problem, and hoping the best for her equipment. Mrs. Roberts hears from me three times, each time with demand to see the magistrate, as I am in jail unlawfully, and have right to immediate adjudication.

➤ Basilio. In the first cell into which Sheriff Garrett’s staff puts me after being seized of my shoes, billfold, bow tie and other valuables is a man who speaks not a lick of American. I meet him 30 minutes later in another holding cell. Sitting next to him on one of two raised bedsteads, on his blanket, we attempt to communicate, but it’s a deadend.

Here’s exactly what we say, a dozen times.

My name is Basilio. My wife’s name is Jessica. My daughter’s name Jasmini. I live in Chattanooga. I live in an apartment. I live in apartment in Chattanooga. I am from Guatemala. I work in construction.

He indicates his daughter is 6 but we don’t work on that since he is called out. He comes back. I’m called out. I come back.

➤ Officer Klinkenfuss is walking behind me back to the holding cell. “Charles Dickens, who wrote Christmas Carol and Bleak House, carried around with him a notepad and record unusual names among Englishmen he met. Had he been a German, he most certainly would have stopped, asked you your name, pulled out his notepad and written ‘Klinkenfuss’ in it” as a name without compare.

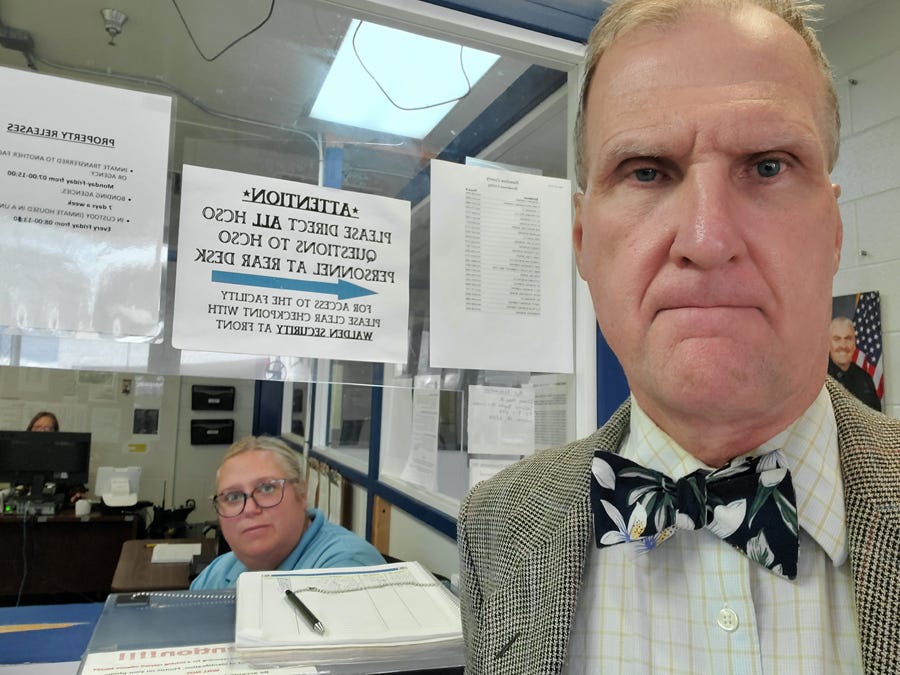

➤ The most important person in the steel and rock sinews of Silverdale is Blake Murchison, the magistrate. Behind a thick glass, as in a cluttered bank office, he sits in front of a computer monitor, from which he read the affidavit of complaint by Deputy Bennett. A printer behind him, he says, doesn’t allow him to print the document for me to examine, he says. And he tilts his monitor my way to see the screen, but the angle is too great. He listens intently to my analysis of the charging instrument, and my discussion about the requirements for arrest. But, it seems, to him, these are remote, theoretical possibilities that to me, when outside, are clear constitutional certitudes. My arguments about travel and the ban on general warrants convince him of one thing: Release on OR, or own recognizance. Clearly, a passion for law is going to bring me to the court.

➤ A begrizzled 30-year-old, a bartender at The Chattanoogan, serves a sentence every Tuesday and Wednesday as the sheriff’s department intends for him to keep his job while also serving his punishment. He has very wild black hair like a 1960s rocker or war protester, and much of the time lies on his side, completely hidden in a blanket.

➤ Man is accused of misdemeanor theft of a bicycle, but he indicates that there’s an explanation for how it is he has come under the supervision of the sheriff’s department after a security man with a monitoring camera and screen sees him take a bike. He is willing to tell me the reasonable explanation.

➤ As I lean over the counter prior to departure I speak with salty-tongued Mrs. Bedwell, who clutches my bag of property she is asking me to sign for. She tells me about her carrier. Mrs Bedwell has my bag of property and is ready to relinquish it to be. She tells about how long she has been in the sheriff’s department and in public service in jails.

➤ A man accused of a serious crime asks me to pay his bond. He has had two cars towed after his arrest. Most of the time of my jailing he is lying on the floor, huddled in a blanket, his head propped on his orange crocks as pillow.

➤ We watch a man in a holding cell with dreadlocks be surrounded by five deputies. They are saying he must leave the small one-person cell because it is needed to hold another prisoner. It takes him 5 minutes to get himself together, though everyone in the unit has no personal property. “Step back,” a deputy tells me.

➤ After I have been processed out and I’m waiting in the public area next to the scanner, a young woman in the shabbiest trousers stands by, heaving and about to burst into sobs. The woman behind the glass at the scanner says that she has been speaking of a past trauma and is in a very emotional state. I shift to a further chair and offer her to sit down, and I am willing to listen to her. The deputy appears to be trying to protect this woman from having to make a conversation with me, which she believes somehow is inevitable. “You don’t have to talk to him,” she tells the woman. “Ma’am this is a public space. we are adults. Let her sit down and let her talk with me.”

“You should mind your own business,” the jailer says. “Please do not talk to her.” She calls two burly deputies who order me out of the room.

“Shame on you,” I tell the woman.

Surrounding me, the deputies herd me through the glass doors, tell me to sit outside in the chill on the bench. But there is an overhead heater in which I bask, waiting for Tim Kochis, a radio engineer, to come and pick me up to get my seized car across the Tennessee River at a Hixson wrecker lot.