How TN tax boss views program to ban poor from roads, boost insurance industry, lie about 'financial responsibility' law

Two cars revoked in bid to challenge industrial-scale op run by department of revenue in Nashville

It is not good to show partiality to the wicked, Or to overthrow the righteous in judgment.

— Proverbts 18:5

Motion to reconsider final agency order

The following motion to reconsider final order is based on a summary of department of revenue (“revenue” or “DOR”) policy administering the state’s financial responsibility (“FR) law in a way to make Part 2 of the law, the Atwood amendment (“Atwood” or “Part 2”), contradict and abrogate Part 1, the Tennessee financial responsibility law of 1977 (“TFRL”), the consequence being to oppress petitioner and the people of Tennessee in departure from law. The electronic insurance verification system (“EIVS”) run by respondent is a data mining utility to help the department administer and enforce Part 1, under supervision of department of safety and homeland security (“safety” or “DOSHS”), specifically T.C.A. § 55-12-139, the penalty provision of the law.

SUMMARY OF DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE POSITION

A. ‘Certified’ is not defined

Certification requirement for auto liability policy that constitutes “evidence” or “proof” of financial responsibility, T.C.A. § 55-12-102, is of no authority to department because the “word ‘certified’ is not a defined term for purposes of chapter 12” (final order, FN 44, p. 17) (emphasis added).

“Certified” is not defined in chapter 12, and respondent is not required to consider EIVS purpose at T.C.A. § 55-12-202 to monitor motor vehicle liability policies, defined in accordance with standards adopted in T.C.A. § 55-12-203 from Insurance Industry Committee on Motor Vehicle Administration (“IICMVA”), and thusly respondent uses no filter in EIVS to (1) separate out and (2) verify motor vehicle liability policies, such policies focus of Atwood, the list operating with no filter allowing DOR to make a list of all uninsureds.

Respondent creates a list of uninsured motor vehicle registrants whom it targets for revocation apart from Atwood authority pursuant to certified policies, but “[p]etitioner’s arguments related to policy certification language found in TFRL do not warrant adjustment of the Initial Order” (final order p. 17).

B. Non-certified = certified

A certified motor vehicle liability policy that is evidence or proof of FR or security is no different legally than a non-certified owner’s or operator’s policy.

Petitioner’s non-certified 2000 Honda Odyssey minivan owner’s policy, the lapsing of which prompted departmental tag revocation “within its statutory authority” (final order p. 11) July 21, 2023, is the same as motor vehicle liability policy defined in T.C.A. § 55-12-102(7), and is thus subject to EIVS monitoring pursuant to T.C.A. § 55-12-202 (purpose statement of EIVS) and the four-notice revocation sequence in T.C.A. § 55-12-210.

C. Motor vehicle liability policy definition

Respondent admits the definition of motor vehicle liability policy is “‘owner’s policy’ or ‘operator’s policy of liability insurance, certified as provided in § 55-12-120 or § 55-12-121 as proof of financial responsibility, and issued *** to or for the benefit of the person named therein as insured” T.C.A. § 55-12-102(7) (emphasis added) (final order p. 16), but that definition is not binding on department’s use of EIVS because “certified” is not defined and respondent does not use the SR-22 data collected by DOSHS’ financial responsibility division EXHIBIT No. 10, Lanfair transcript pp. 13, 14.

D. Department has No. 1 role in TFRL

Respondent denies subordinate role in the Tennessee FR law, either under the certification requirement for insurance policies to be monitored under EIVS or under DOSHS.

In light of law stating “the commissioner [of safety] shall administer and enforce this chapter,” T.C.A. § 55-12-103, and DOSHS’ financial responsibility division with records of motor carrier policies and people subject to TFRL because of suspension, respondent has independent operation of EIVS.

Whereas “[t]he commissioner of revenue shall develop, implement, and administer an insurance verification program to electronically verify whether the financial responsibility requirements of this chapter have been met with a motor vehicle liability insurance policy; provided, the commissioner may contract with a designated agent to develop, implement, and administer the program. (b) Prior to issuance of a request for proposal for the services of a designated agent or prior to developing and implementing the program, the department of revenue or, if applicable, its designated agent shall consult with the following entities to determine the details and deadlines related to the program: *** (3) The department of safety” T.C.A. § 55-12-204. Motor vehicle insurance; electronic verification program; commissioner duties, respondent does not cooperate with DOSHS, nor monitor the “motor vehicle liability policy” required by law (to the exclusion of other forms of insurance) and need not explain itself in instant case because “[p]etitioner provides no support or citation for his contention that only SR-22 policies are ‘certified’ within the meaning of the definition” (final order p. 17).

For respondent, any insurance is “acceptable” without certificate of proof or evidence (the SR-22 certificate of insurance) as condition of retaining the privilege under motor vehicle registration.

Respondent does not deny the purpose of the electronic insurance verification system (“EIVS”) is to “verify whether the financial responsibility requirements of this chapter have been met with a motor vehicle liability insurance policy,” T.C.A § 55-12-202 (emphasis added), but respondent prevails in the case because “Petitioner provides no support or citation *** that only SR-22 policies are ‘certified’ within the meaning of this definition” (T.C.A. § 55-12-202).

E. Court on ‘certified’ denied

The fact the insurance policy in question is on file and approved by the Commissioner of Insurance and Banking, pursuant to T.C.A. s 56—603, does not make the policy a “certified policy” under our financial responsibility law. McManus v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 225 Tenn. 106, 112, 463 S.W.2d 702, 705 (1971) (emphasis added). Despite incorporation in law of IICMVA standards in T.C.A. § 55-12-203 and -205 on the central role of the certified policy in TFRL, respondent denies IICMVA standards for monitoring the certified policy apply to EIVS.

F. IICMVA explains difference

IICMVA explains the difference between mandatory insurance law and financial responsibility law. “Certification of liability insurance coverage for the future is a basic element in all financial responsibility laws. In order to reinstate a driving privilege after a driver license suspension, an insurance company is called upon to certify liability coverage for the future, usually three years, for the affected individual. While the basic certification concept is for the most part rather uniform among the states having financial responsibility laws,” EXHIBIT No. 9, p. 3, Financial responsibility programs and procedures guide, IICMVA, January 2015; See also MSJ pp. 61, 62, 70 [sample SR-22], 77-84), but respondent alleges Atwood “directs the Department to check vehicle registrations against insurance company records to verify active liability insurance coverage” (final order p. 9). See APPENDIX II, IICMVA “Financial Responsibility Programs and Procedures Guide,” January 2015, pp. 1-7, 47, 48 (Tennessee), p. 3, paragraph 3

G. 210 ‘insurer of record,’ ‘eligible for notice’ clues

In T.C.A. § 55-12-210, party who has certified motor vehicle liability policy is subject to respondent monitoring, “(g) If the vehicle is no longer insured by the automobile liability insurer of record and no other insurance company using the IICMVA model indicates coverage after an unknown carrier request under § 55-12-205(3), the owner of the motor vehicle becomes eligible for notice as described in subsections (a) and (b)” (emphasis added), but “[p]etitioner’s reading of the TFRL and the Atwood Law is not supported by the plain language of the statutes” (final order p. 11).

H. Overruling IICMVA standard

The IICMVA handbook says SR-22s are “future proof of insurance certificates” required in any of four situations, including “unsatisfied judgment, driver license suspension as a result of a major conviction, conviction point system suspension,” or “failure to establish financial responsibility as result of an accident” (MSJ pp. 47, 48), but respondent in reference to IICMVA (initial order p. 27) (“the verification program was required to meet ‘IICMVA specifications and standards’”) does not accept the IICMVA standard as limiting scope of EIVS use as some insurers “choose[ ] not to utilize the IICMVA model, to ‘provide to the department of revenue, or its designated agent, a full book of business’” (initial order p. 28).

Respondent claims authority to not be bound by IICMVA standards in Atwood regarding the “financial responsibility insurance certificate,” T.C.A. 55-12-126, by reference to alternate insurance industry data delivery methods for delivery of the “a full book of business by the seventh day of each calendar month,” implying that because industry must transmit its “full book” that, thusly, every auto insurance customer is subject to a POFR requirement (initial order, p. 28).

I. Not bound by standard

Respondent is under no duty to explain how a non-certified auto insurance policy is otherwise certified and “acceptable,” nor how certified motor vehicle liability policy, defined in § 55-12-102(7), is equivalent to non-certified insurance policy, which latter the orders say is subject of EIVS and the sect. 210 notice sequence.

Revenue handles certificates of registration and FR certificates in title 55, and many other certificates in title 67, but in its role serving department of safety in TFRL denies certification standard.

J. Petitioner fails to establish the law

Petitioner’s sole line of analysis in 15 minutes of oral argument Nov. 22, 2024, is the certification issue, detailed in Brief on abrogated laws in support of motion for summary judgment (“MSJ”) as “DOR”s biggest blooper,” pp. 38-41, and is broadly developed in MSJ (pp. 15, 16, 62, 63, 68, 69, 78-82, 120, 121), but the linchpin role of the certified policy is “not [raised]” timely by petitioner and thus waived (Final order p. 16), and respondent need not argue against “newly articulated” analysis of petitioner’s “New Theory” — nor must it obey the law on certification.

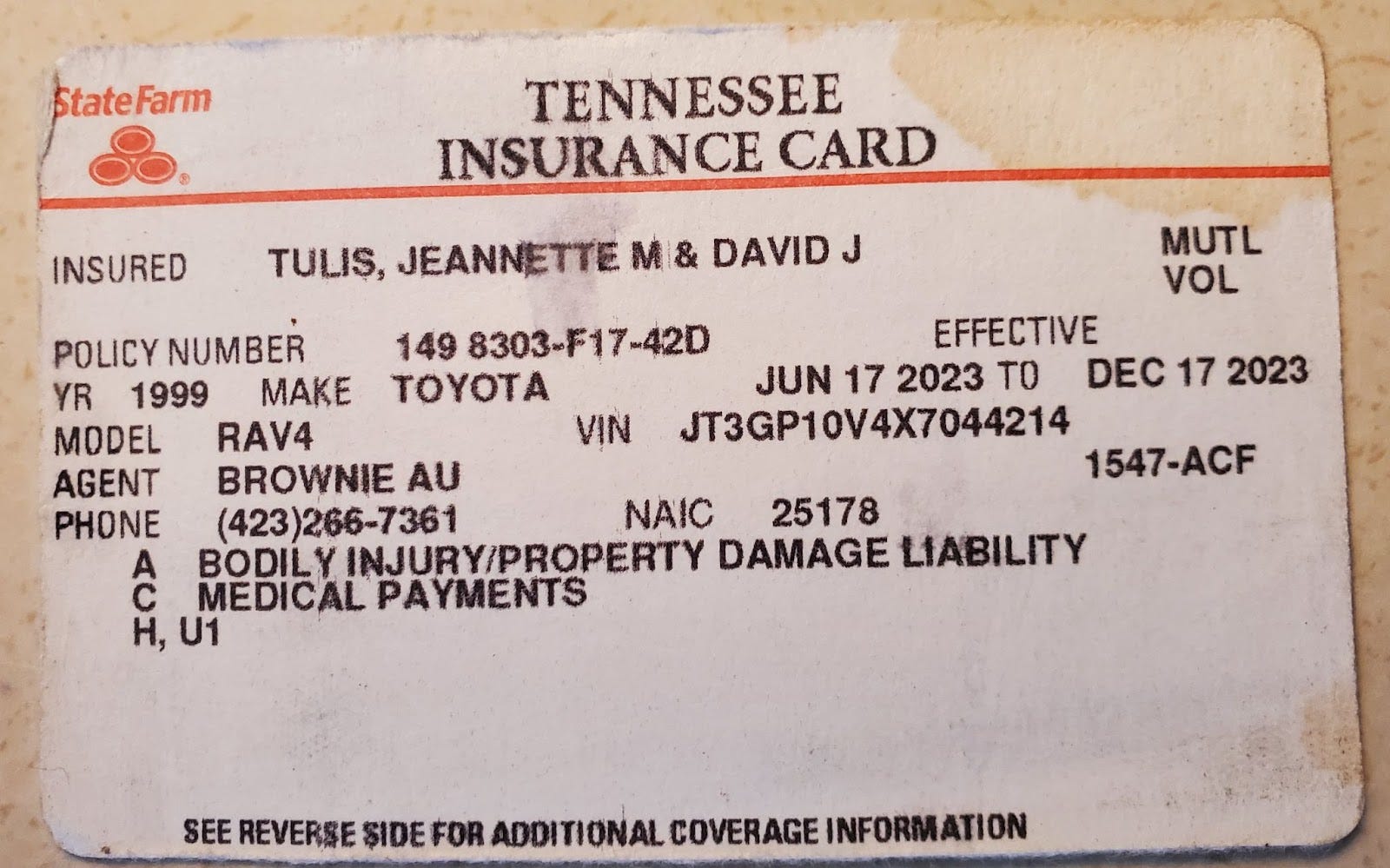

Respondent says the SR-22 financial responsibility certificate (photo top) is

= equal to =

an ordinary insurance wallet billfold card, which DOR says satisfies the commissioner of safety as POFR, despite T.C.A. § 55-12-122 (photo below).

K. Good faith inattention

In FN 41 in final order pp. 15, 16, respondent cites certification material in petitioner 42pp. brief, but such material “does not meaningfully assert any argument relating to policy certification” and DOR does not entertain claims of harm to petitioner.

Respondent does not need to read petitioner brief in support of MSJ to the end where, pp. 38-41, he details certification, which failure is not bad faith nor an abuse of the reviewing court.

L. Nondistinct legal concept

Respondent issues motor vehicle registration certificates, admits using certificates in many formats as evidence, proof, endorsement, guarantee, security, certainty, affirmation of authenticity, promise of veracity, and on p. 19 of final order provides “certificate of service”; yet respondent abrogates the TFRL certification concept to make such usages as “financial responsibility insurance certificate,” T.C.A. § 55-12-126, nondistinct from ordinary operator’s and insurance policy and noncontrolling in operation of EIVS.

Beholding an accident scene, T.C.A. § 55-10-108 describes how a police officer sifts motorist insurance facts differently from the proof of financial responsibility certificate, the officer required to copy the “certificate of compliance with the [TFRL], compiled in chapter 12 of this title, issued by the commissioner of safety, a copy of the certificate shall be included in the report,” but respondent blurs the distinction as irrelevant because the certification issue “is not well taken” (order p. 16).

M. ‘Alleged certification requirement’

Respondent does not deny certification is involved in POFR in insurance alternatives — in the $65,000 cash or corporate “bond” and “notarized releases executed by all parties who had previously filed claims with the department as a result of the accident” T.C.A. § 55-12-105, have certification or oath-bound components, but respondent avers the SR-22 certificate for the “motor vehicle liability policy” defined at T.C.A. § 55-12-102(7) is only an “alleged certification [requirement] *** for purposes of EIVS compliance” (final order p.15) (emphasis added).

Certification of a policy by the insurer is in a form approved by the commissioner of safety. “Whenever, under this part, any person is required to file with the commissioner of safety acceptable evidence of security, proof of financial responsibility, and the requirement may be satisfied by written proof of insurance coverage in the amounts required by this part, and the person is so insured, it is the duty of the insurance company with whom the person has insurance to file, upon request of the insured, the necessary information with the commissioner on a certificate or form approved by the commissioner.” § 55-12-137. Filing proof of insurance, but respondent says a wallet card or insurer declaration is acceptable evidence or proof of POFR and his numerous citations to the certified policy requirement are “not well taken” (final order p. 16).

Respondent, despite extensive petitioner material on reading law in pari materia, certification of the motor vehicle liability policy and EIVS’ role monitoring motor vehicle probationers, says petitioner “does not specify whether or why the alleged deficiency in coverage certification should result in the reinstatement of his vehicle registration” and that petitioner “mistakenly assumes that certain Part 1 provisions have bearing on the Department’s administration of EIVS under Part 2, when in fact they do not” (final order p. 16).

Petitioner, reading all parts of the law in pari materia, persists in a “continuation of his pattern to conflate the requirements of the TFRL with the requirements of the Atwood Law” that creates “‘independent and parallel processes’ for enforcing financial responsibility” (final order p. 16).

SCREENGRAB of TFRL FLOWCHART EXHIBIT

Respondent doubts that the certificate referred to in chapter 12 is the industry standard for license suspended licensee coverage is called the SR-22 and the meaning of the law is not plain or directive.

N. Good faith assistance of petitioner 2 years

These doubts exist despite petitioner’s July 2023 administrative notice regarding TFRL limits and nearly two years of legal assistance to state government about industry protocols incorporated into the law in IICMVA standards (MSJ pp. 77ff.) EXHIBIT No. 11 (IICMVA white paper, “The Case for Utilizing Web Services Technology to File Certificates of Financial Responsibility”).

Petitioner unnumbered EXHIBIT (“Tulis TFRL flowchart VER2”) shows a coherent non-conflicted whole in the financial responsibility law, but respondent justly and properly ignores harmony of law laid out in the flowchart in favor of self-contradiction and consequent departure from law, further breaking other citizen-protection guardrails such as 18 U.S.C. 241; U.S. Const. Art 1, sect. 9, clause 3 attainder ban (MSJ pp. 153ff, Appendix II, administrative notice of law violations), with respondent saying petitioner revocation was “properly undertaken” (final order p. 11).

O. DOSHS goes it alone in developing EIVS

Though in T.C.A. § 55-12-103 the commissioner of safety “shall administer and enforce this chapter,” the department admits it developed EIVS and operates the system without input from safety on grounds of its program’s “independent and parallel processes” (final order p. 17).

Revenue did not consult with safety as to petitioner’s good driving record, nor consult with safety’s financial responsibility division with its records of all SR-22 certificates that are “acceptable evidence of security,” T.C.A. § 55-12-137, revoking petitioner on its own authority by automated process by contractor i3 Vertical with no human intervention (department witness Jennifer Lanfair transcript, pp. 13-15, EXHIBIT No. 10).

Department says it uses the doctrine of reading law in pari materia, but applies the concept of in pari materia only to those provisions that support existing policy, leading to a proper ruling in its favor in the contested case (initial order pp. 34, 35) and “undertaken in accordance with the Department’s mandate” (final order p. 11)

P. 28 abrogations invalid

Respondent need not deny evidence of 28 abrogated provisions because its program is an “independent and parallel suspension/revocation [process]” (initial order p. 34) from the financial responsibility law in chapter 12. “I agree with the Department *** that the General Assembly enacted the Atwood Law to create a separate enforcement mechanism for the [FR] requirements that operates independently from the post-accident reporting regime overseen by DOSHS under Tenn. Code Ann. § 55-12-104-106” (initial order pp. 32, 33).

TFRL imposes monitoring and strict scrutiny of drivers adjudicated to be high risk who agreed to maintain evidence or proof of FR for a set period of time. “The licensee shall maintain such proof of financial responsibility for the duration of the license’s suspension or revocation, as required by § 55-12-126” T.C.A. § 55-12-114. Respondent voids many parts of the law, including § 55-12-114, claiming suspension authority over all motor vehicle users, absent a qualifying accident or an adjudication against such registrations.

Q. Hearing under tax code

Respondent holds hearing for its TFRL allegations though T.C.A. § 55-12-103 says the commissioner of safety holds hearings for TFRL disputes, but petitioner has no standing to make appeal to safety for his grievance, indicating violation of his right to due process from which harm respondent saves him by holding this contested case.

Though “[t]he parties cannot confer subject matter jurisdiction on a trial or appellate court by appearance, plea, consent, silence, or waiver” In re Est. of Trigg, 368 S.W.3d 483, 489 (Tenn. 2012), respondent orders issue in instant case from hearing under the state tax code, as “Department plainly has jurisdiction to convene this contested case” (initial order p. 19), citing T.C.A. § 67-1-105, with petitioner’s pursuing his rights in agency (“willingly availed himself,” initial order, p. 20) curing the jurisdictional defect.

R. Court rulings persuasive

The courts describe TFRL as a financial responsibility law and not as mandatory insurance law, but respondent is not bound by court rulings, even after 2002, in which § 55-12-139 took effect.

In 2005, a court states,

Tennessee first enacted a Financial Responsibility Law in 1949. 1949 Tenn. Pub. Acts ch. 75 (effective July 1, 1949); see also The Tennessee Motor Vehicle Financial Responsibility Act, 21 Tenn. L.Rev. 341, 342 (1950). The current law was enacted in 1977, see Tenn.Code Ann. § 55–12–101, but its core provisions are largely unchanged from the 1949 law. Compare 21 Tenn. L.Rev. at 342–43 with Tenn.Code Ann. §§ 55–12–104–05.

Briefly, the Financial Responsibility Law requires motorists who have been involved in an accident where anyone is killed or injured, or an accident resulting in more than $400 in damage to the property of any one person, to show proof of financial responsibility. Tenn.Code Ann. § 55–12–105; see also id. § 55–12–139. Failure to comply can result in revocation of the motorist's license and registration. Id. § 55–12–105. As amended in 2001, the law requires drivers to provide proof of financial responsibility to an officer at the scene of an accident or a moving violation. Id. § 55–12–139(b). Failure to comply is a Class C misdemeanor punishable by a fine of up to $100. Id. § 55–12–139(c).

67 The purpose of Tennessee's Financial Responsibility Law is to protect innocent members of the public from the negligence of motorists on the roads and highways. Specifically, “[t]he financial responsibility laws of this State are concerned with the ability of an automobile driver to pay for bodily injury and property damage for which he may be legally liable.” Schultz v. Tenn. Farmers Mut. Ins. Co., 218 Tenn. 465, 404 S.W.2d 480, 484 (1966). The Financial Responsibility Law is not, however, a compulsory insurance law. McManus v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 225 Tenn. 106, 463 S.W.2d 702, 703 (1971). Although the law applies to “every vehicle subject to the registration and certificate of title provisions,” Tenn.Code Ann. § 55–12–139(a) (eff. Jul. 1, 2005), as we have previously explained,

the Legislature stopped short of requiring public liability insurance as a condition precedent to the owning or operating of a motor vehicle. The sanctions of this statute are not involved unless and until the owner or operator is involved in an accident resulting in bodily injuries or property damage in excess of $[400.00]1; until such occurs a person is at liberty to own and operate a motor vehicle without any insurance coverage or with as little insurance coverage as desired.

Id.

Although the Financial Responsibility Law does not, by its express terms, require *707 drivers to obtain liability insurance in order to comply, the Law clearly contemplates that most drivers will comply by purchasing liability insurance. For this reason, the Financial Responsibility Law also sets forth requirements for the contents of motor vehicle liability policies. Tenn.Code Ann. § 55–12–122. The law requires that motor vehicle liability policies “shall insure the person named therein, and any other person using any such motor vehicle or motor vehicles with the express or implied permission of such named insured, against loss from the liability imposed by law for damages arising out of the ownership, maintenance, or use of such motor vehicle....” Id. § 55–12–122(a).

Purkey v. Am. Home Assur. Co., 173 S.W.3d 703, 706–07 (Tenn. 2005) (emphasis added)

TFRL may persuade the public and while “most drivers will comply by purchasing liability insurance,” the law does not “require” insurance as a universal obligation, but DOR all members of the public under color of T.C.A. § 55-12-210, which describes department duties for notice, and T.C.A. § 55-12-139 stating “officer shall request evidence of financial responsibility as required by this section” T.C.A. § 55-12-139(b)(1).

S. Sect. 139 = full rewrite of financial responsibility law

Respondent denies that Atwood is an amendment limited to improving supervision of license suspendees following safety or court adjudication under T.C.A. § 55-12-139, but sees is a law creating a new, second FR regime in Tennessee, as if the general assembly had done a full rewrite of financial responsibility legislation (initial order p. 25).

Respondent fills enforcement gaps left by safety, which receives reports about accidents, T.C.A. § 55-12-104 and -105, and supervises parties suspended for cause in court cases, T.C.A. § 55-12-114 and -115 under findings of fault.

T.C.A. § 55-12-139(b)(1) says documentation of insurance must state the policy meets requirements of Part 1 of it being certified:

For the purposes of this section, “financial responsibility” means:

(A) Documentation, such as the declaration page of an insurance policy, an insurance binder, or an insurance card from an insurance company authorized to do business in this state, whether in paper or electronic format, stating that a policy of insurance meeting the requirements of this part has been issued;

(B) A certificate, valid for one (1) year, issued by the commissioner of safety, stating that:

(i) A cash deposit or bond in the amount required by this part has been paid or filed with the commissioner of revenue; or

(ii) The driver has qualified as a self-insurer under § 55-12-111[.]

Though certification requirements control sect. 139, respondent uses T.C.A. § 55-12-139(a) to brush aside statutory particulars of whom is liable under TFRL and subject to performance.

“[T]he post-accident reporting procedures administered by DSHS under the TFRL operate independently from the Department’s administration of the EIVS Program under the Atwood Law” (final order p. 12). The two departments’ programs “may operate fully in parallel with the other” and “suspension may occur under an entirely different set of circumstances—the identification by the Department [of revenue] that a vehicle owner does not maintain liability insurance on the vehicle” (final order p. 13), with safety ordering revocation of license (and, as upon respondent, upon tag) under one standard and respondent under a different standard.

“If there is evidence based on either the IICMVA model or the full book of business download process described in § 55-12-207 that a motor vehicle is not insured, the department of revenue shall, or shall direct its designated agent to, provide notice to the owner” of noncompliance. T.C.A. § 55-12-210 (emphasis added). The words “a motor vehicle” refers to any motor vehicle in the state, their meaning not bound by the rule of reading law in pari materia that constrains meaning of this phrase as controlled by chapter 12.

T. Sect. 210 compels sending, receiving notices

Thus respondent justly uses EIVS to revoke petitioner: “This statutory directive [T.C.A. § 55-12-210(c)(1)-(2)] is clear – when the EIVS program identifies a vehicle as unconfirmed and the registrant fails to cure EIVS noncompliance in response to the first three Notices, the Department is required to suspend the registration” (final order p. 10).

Petitioner erroneously imposes “limitations on the EIVS Program that are not present in the text of Section 210” (final order p. 13), and Atwood isn’t merely a utility to monitor motor vehicle liability policies required of parties under sect. 114 suspension, but authorizes an entirely separate enforcement mechanism in which all registrants are presumptively irresponsible, including denying 11 exemptions in Part 1 (T.C.A. § 55-12-104) such as accident without contact with another vehicle, relevant to petitioner as accident-free.

Sect. 214 is not violated by respondent because “Per Section 214, the Atwood Law does not change the universe of vehicles to which the TFRL applies, but that universe was already expanded by the enactment of Section 55-12-139(a)” (initial order p. 30)

Because T.C.A. § 55-12-210 doesn’t repeat T.C.A. § 55-12-214 (“Nothing in this part shall alter the existing financial responsibility requirements in this chapter”), DOR is required to send notices to all motor vehicle owners who do not connect a policy to a VIN demanding compliance or revoking them.

U. Identify ‘uninsured vehicles’

“I have concluded that the TFRL and the Atwood Law together authorize and direct the Department of Revenue to create the EIVS Program and use it to identify uninsured vehicles” and that respondent “properly and lawfully suspended Petitioner’s vehicle registration under” T.C.A. § 55-12-210 (final order p. 11, quoting initial order).

V. Revise rule ejusdem generis

Though “independent” of Part 1, respondent’s EIVs program is authorized by T.C.A. § 55-12-139(a), “This part shall apply to every vehicle subject to the registration and certificate of title provisions” (with which respondent alleges petitioner does not “engage” (final order p. 13)), which is permitted to respondent because while the statutory construction rule ejusdem generis constrains reading of law so that specific provisions constrain scope of meaning of general ones, courts may accept respondent revision: “A more general provision takes precedence over a specific statutory provision” (See MSJ pp. 25, 31, 130). APPENDIX No. 1, incorporated herein by reference.

W. ‘Modified universe’

In revising the construction rule, respondent brings new meaning to § 55-12-139, which states, “If the driver of a motor vehicle fails to show an officer evidence of financial responsibility, or provides the officer with evidence of a motor vehicle liability policy as evidence of financial responsibility, the officer shall utilize the vehicle insurance verification program as defined in § 55-12-203 and may rely on the information provided by the vehicle insurance verification program, for the purpose of verifying evidence of liability insurance coverage,” which provision respondent revises to delete the limiting language of “motor vehicle liability policy” because sect. 139 “modified the universe of vehicles covered by the subsection and reiterated that they are subject to ‘this chapter,’ i.e., the requirements of financial responsibility laid out in the chapter” (initial order p. 25).

Respondent is authorized to abrogate many parts of chapter 12 under vast power of T.C.A. § 55-12-139(a), which petitioner calls a “geyser of authority” (petition for agency review p. 17) that defies the judicial standard viewing with disfavor abrogation by implication.

X. Safe driver penalty

Because sect. 139(a) universalizes the obligation for POFR, respondent makes accident-free, safe licensees such as petitioner face the same penalty as do suspended drivers adjudicated financially irresponsible who keep the driving privilege on condition precedent of having a motor vehicle liability policy, the premium upkeep of which is monitored by EIVS pursuant to T.C.A. § 55-12-202.

Y. Department revised policy

Respondent is free to alter policy goals set forth in the statute under IICMVA standards. “The IICMVA’s manual for describing how financial responsibility laws operate agrees with petitioner’s analysis about the scope of TRFL. Such laws ‘require owners of motor vehicles to produce proof of financial accountability as a condition to acquiring a license and registration so that judgments rendered against them arising out of the operation of the vehicles may be satisfied. It is generally accepted, as a condition for operating on a state’s roadways, a driver has agreed to be financially responsible for any harm or damage caused through the operation of his or her vehicle’” (quoting MSJ p. 78) (emphasis added).

Z. ‘Bar such motorists’ who lack ‘established capacity’

Respondent final order targets for notice and revocation not just those adjudicated irresponsible whose privilege is suspended, T.C.A. § 55-12-126, but the poor who lack “established [financial] capacity,” (final order p. 8), low-income, hard-by working class people such as petitioner who are irresponsible and revocable insurance industry noncustomers.

Final and initial order agree on targeting the poor. “[O]wners and lessees of vehicles that are registered for on-road use must demonstrate financial responsibility, which is a term that refers to the registrant’s established capacity to recompense injury or damage sustained in the event of an accident” (Christine Lapps, final order p. 8) (emphasis added). “If someone is unable to meet the financial burden of proving financial responsibility their ability to pay for damages they may cause in the operation of their vehicle is necessarily also in question. It is the intent of the General Assembly in enacting the TFRL to bar such motorists from operating on the highways of this state.” (Brad Buchanan, initial order p. 31) (emphasis added). No agency except department revenue is authorized to alter the purpose of a law and shift its moral framework of duty and punishment.

AA. ‘Duration of license’s suspension’

Final order, in defeating the petition, focuses on the accident reporting provisions of TFRL — the backward-looking part of the statute in which qualifying accident parties show POFR by SR-22 certificate under T.C.A. § 55-12-104 that petitioner is allegedly obsessed by — while ignoring the forward-looking aspect of the law overseeing suspension and insurance monitoring under T.C.A. § 55-12-114 and -116, which provisions include: “The licensee shall maintain proof of financial responsibility for the duration of the license’s suspension or revocation, as required by § 55-12-126,” in T.C.A. § 55-12-116, and rules on restricted licenses in T.C.A. § 55-12-114, such as, “The licensee shall maintain such proof of financial responsibility for the duration of the license’s suspension or revocation, as required by § 55-12-126. (c) When a person's license is restored after suspension or revocation, the person shall pay a one-hundred-dollar restoration fee,” with DOR denying EIVS duty to monitor these registrants only.

Final order denies the distinction between certified motor vehicle liability policies as defined in T.C.A. § 55-12-102(7) and all other policies, letting respondent extort all uninsured registrants as “unconfirmed” (final order pp. 9, 10) and liable for punishment for not obtaining non-certified owner or operator insurance policies.

BB. Respondent obedience begets obedience

Initial and final orders, under a “[revised] *** universe” in T.C.A. §§ 55-12-139 and -210, express no alarm at what petitioner calls irregularity and contradiction, these considered “acceptable.”

➤ The law grants exceptions, T.C.A. § 55-12-106, but DOR denies them;

➤ The law halts suspension terms (“If the department of safety *** releases the requirement that a person furnish proof of financial responsibility,” T.C.A. § 55-12-116;

➤ “[T]he department of safety *** releases the requirement that a person furnish proof of financial responsibility *** ” T.C.A. § 55-12-126, but DOR says suspension is forever;

➤ Licensee on suspension retains the privilege by a motor vehicle liability policy defined in § 55-12-102(7), but respondent says all motorists must obtain such policies or be suspended;

➤ T.C.A. § 55-12-105 on qualifying accidents says “submission to the commissioner of notarized releases executed by all parties who had previously filed claims with the department [of safety] as a result of the accident” constitutes proof of financial responsibility and satisfaction of the law, but respondent revokes them for not being insured or bearing “evidence” of POFR;➤ A person who pays DOSHS a cash bond to cover costs of an accident, shows POFR by the payment, and is revoked by respondent for lacking “present POFR” or “future oriented POFR” demanded by suspended persons under T.C.A. § 55-12-114 who agree to be insured on condition of privilege;

➤ T.C.A. § 55-12-102(7) says a motor vehicle liability is “certified as [POFR]”, but DOR requires POFR of all motorists and requires uncertified insurance wallet card or declarations page as “evidence” or “proof” of financial responsibility;➤ T.C.A. § 55-12-210 says SR-22 insureds are “eligible for notice” if the insurer notifies safety of lapsed (nonpayment) policy, but DOR says insurance noncustomers are “eligible” for revocation notice under T.C.A. § 55-12-210;

➤ Failure of person with suspended license to maintain the motor vehicle liability policy brings insurance company notice to department of safety and revocation by DOSHS and DOR in T.C.A. § 55-12-123, but respondent says any motor vehicle registrant without a non-certified policy is revoked;

➤ T.C.A. § 55-12-130 says “it is unlawful” for revenue to restore a tag apart from written permission by safety commissioner, but DOR says it’s not and will renew petitioner’s tag if he joins ranks of State Farm, Grange or Progressive customers.

Instant case is about statutory construction with no material facts in dispute, with respondent confident the courts will sacrifice longstanding stabilizing rules of construction and accept extortion and denial of due process as a public benefit.

CC. 40,832 convictions annually shows TFRL protects public

The commissioner annually reports to the general assembly convictions under TFRL, 40,832 per year over eight years, or 77,748 convictions since petitioner filed for contested case July 26, 2023, 695 days ago, this report evidence of the effect of respondent’s interpretation of TFRL and Atwood, described on its website: “The James Lee Atwood Jr. Law (also referred to as the electronic insurance verification program) imposes insurance requirements on motor vehicles operated on Tennessee roads” (emphasis added), which Atwood amendment states, “Nothing in this part shall alter the existing financial responsibility requirements in this chapter” T.C.A. § 55-12-214. Financial responsibility requirements unaffected (emphasis added); hence, the 77,748 convictions among the poor are valid and lawful use of police power and not evidence of harm or official misconduct, extortion or official oppression, as alleged.

TFRL requires the poor to buy insurance they cannot afford to obtain policies that are not legally sufficient as POFR, or be revoked, and thus “[b]ased on the foregoing, it is hereby ORDERED that *** [t]he petition is denied and dismissed” (final order p. 18).

RECONSIDERATION REQUEST

In light of the foregoing skein of irregularity by respondent, petitioner asks the agency to rescind its final order — to (1) restore petitioner’s tag and (2) admit its program is arbitrary, capricious and a departure from law in breach of trust and injury to relator and the public at large. Petitioner is put into the legally untenable position of being unable to comply with the “law” as put forth by respondent. Even if he had ordinary, non-certified insurance, that insurance would not comply with the law because only a certified motor vehicle liability policy is proof of financial responsibility, T.C.A. § 55-12-102(7).

The case record is clear. T.C.A. § 55-12-102(7) defines a motor vehicle liability policy as one certified as proof of financial responsibility, which concept is borne in the name of the statute, which certification document is the well-established and well-known SR-22 financial responsibility certificate (MSJ p. 70) described in detail in this case in oral argument and motion for summary judgment (and its supporting brief), which respondent in bad faith and official misconduct ignores.

Respondent’s agenda and policy creates a program that is unconstitutional, violating petitioner’s constitutional rights. APPENDIX III. The program is unconstitutional because it is arbitrary, impermissible and oppressive, which acts are forbidden under ordinary rules of statutory construction, as cited in APPENDIX I reminding the department of its authorities, appendices each incorporated herein by reference.

Respectfully submitted,

David Jonathan Tulis

Appendix I

Rules of statutory construction summary

‘Construe statutes as we find them’

The responsibility for determining what a statute means rests with the courts. Roseman v. Roseman, 890 S.W.2d 27, 29 (Tenn.1994); Realty Shop, Inc. v. R.R. Westminster Holding, Inc., 7 S.W.3d 581, 601 (Tenn.Ct.App.1999). We must ascertain and then give the fullest possible effect to the General Assembly’s purpose in enacting the statute as reflected in the statute's language. Stewart v. State, 33 S.W.3d 785, 790-91 (Tenn.2000); Lavin v. Jordon, 16 S.W.3d 362, 365 (Tenn.2000). In doing so, we must avoid constructions that unduly expand or restrict the statute’s application. Watt v. Lumbermens Mut. Cas. Ins. Co., 62 S.W.3d 123, 127-28 (Tenn.2001); Patterson v. Tenn. Dep't of Labor & Workforce Dev., 60 S.W.3d 60, 64 (Tenn.2001); Limbaugh v.. Coffee Med. Ctr., 59 S.W.3d 73, 83 (Tenn.2001). Our goal is to construe a statute in a way that avoids conflict and facilitates the harmonious operation of the law. Frazier v. East Tenn. Baptist Hosp., Inc., 55 S.W.3d 925, 928 (Tenn.2001); LensCrafters, Inc. v. Sundquist, 33 S.W.3d 772, 777 (Tenn.2000).

Our construction of a statute is more likely to conform with the General Assembly’s purpose if we approach the statute presuming that the General Assembly chose its words purposely and deliberately, Tidwell v. Servomation-Willoughby Co., 483 S.W.2d 98, 100 (Tenn.1972); Merrimack Mut. Fire Ins. Co. v. Batts, 59 S.W.3d 142, 151 (Tenn.Ct.App.2001), and that the words chosen by the General Assembly convey the meaning the General Assembly intended them to convey, Limbaugh v. Coffee Med. Ctr., 59 S.W.3d at 83; BellSouth Telecomms., Inc. v. Greer, 972 S.W.2d 663, 673 (Tenn.Ct.App.1997). Thus, we must construe statutes as we find them, Jackson v. Jackson, 186 Tenn. 337, 342, 210 S.W.2d 332, 334 (1948); Pacific Eastern Corp. v. Gulf Life Holding Co., 902 S.W.2d 946, 954 (Tenn.Ct.App.1995), and our search for a statute’s purpose must begin with the words of the statute itself, Blankenship v. Estate of Bain, 5 S.W.3d 647, 651 (Tenn.1999); State ex rel. Comm'r of Transp. v. Medicine Bird Black Bear White Eagle, 63 S.W.3d 734, 754 (Tenn.Ct.App.2001).

‘Interpret them as written’

We must give a statute’s words their natural and ordinary meaning unless the context in which they are used requires otherwise. Frazier v. East Tenn. Baptist Hosp., Inc., 55 S.W.3d at 928; Mooney v. Sneed, 30 S.W.3d 304, 306 (Tenn.2000); State v. Fitz, 19 S.W.3d 213, 216 (Tenn.2000). Because words are known by the company they keep, State ex rel. Comm’r of Transp. v. Medicine Bird Black Bear White Eagle, 63 S.W.3d at 754, we should construe the words in a statute in the context of the entire statute and in light of the statute’s general purpose, State v. Flemming, 19 S.W.3d 195, 197 (Tenn.2000); Lyons v. Rasar, 872 S.W.2d 895, 897 (Tenn.1994); Wachovia Bank of N.C., N.A. v. Johnson, 26 S.W.3d 621, 624 (Tenn.Ct.App.2000). When the meaning of statutory language is clear, we must interpret it as written, Kradel v. Piper Indus., Inc., 60 S.W.3d 744, 749 (Tenn.2001); ATS Southeast, Inc. v. Carrier Corp., 18 S.W.3d 626, 629-30 (Tenn.2000), rather than using the tools of construction to give the statute another meaning, Limbaugh v. Coffee Med. Ctr., 59 S.W.3d at 83; Gleaves v. Checker Cab Transit Corp., 15 S.W.3d 799, 803 (Tenn.2000).

‘Cautious about consulting legislative history’

Statutes, however, are not always free from ambiguity. When we encounter ambiguous statutory language-language that can reasonably have more than one meaning10-we must look to the entire statute, the entire statutory scheme in which the statute appears, and elsewhere to ascertain the General Assembly’s intent and purpose. State v. Walls, 62 S.W.3d 119, 121 (Tenn.2001); State v. McKnight, 51 S.W.3d 559, 566 (Tenn.2001). One of the sources that we frequently look to for guidance is the statute’s legislative history. Bowden v. Memphis Bd. of Educ., 29 S.W.3d 462, 465 (Tenn.2000); Hathaway v. First Family Fin. Servs., Inc., 1 S.W.3d 634, 640 (Tenn.1999); Reeves-Sain Med., Inc. v. BlueCross BlueShield of Tenn., 40 S.W.3d 503, 507 (Tenn.Ct.App.2000). We must be cautious about consulting legislative history. BellSouth Telecomms., Inc. v. Greer, 972 S.W.2d at 673. A statute’s meaning must be grounded in its text. Thus, comments made during the General Assembly’s debates cannot provide a basis for a construction that is not rooted in the statute’s text. D. Canale & Co. v. Celauro, 765 S.W.2d 736, 738 (Tenn.1989); Townes v. Sunbeam Oster Co., 50 S.W.3d 446, 453 n. 6 (Tenn.Ct.App.2001). When a statute’s text and the comments made during a legislative debate diverge, the text controls. BellSouth Telecomms., Inc. v. Greer, 972 S.W.2d at 674.

The tasks of statutory construction and applying a statute to a particular set of facts involve questions of law rather than questions of fact. Patterson v. Tenn. Dep’t of Labor & Workforce Dev., 60 S.W.3d at 62; State v. McKnight, 51 S.W.3d at 562; Myint v. Allstate Ins. Co., 970 S.W.2d 920, 924 (Tenn.1998). Accordingly, appellate courts must review a trial court’s construction of a statute or application of a statute to a particular set of facts de novo without a presumption of correctness. State v. Walls, 62 S.W.3d at 121; Hill v. City of Germantown, 31 S.W.3d 234, 237 (Tenn.2000); Mooney v. Sneed, 30 S.W.3d at 306.

Midwestern Gas Transmission Co. v. Green, No. M200500796COAR3CV, 2006 WL 464115, at *3–5 (Tenn. Ct. App. Feb. 24, 2006) (emphasis added)

Appendix II

Constitutional violations arising from breach of law

The God-given, constitutionally guaranteed, unalienable and inherent rights of petitioner abused by respondent in this case are that of (1) use of the public roads forbidden because respondent doesn’t recognize nonprivileged use of the public way during pendency of proceeings, the (2) right to have and use property, whether that of private chattel (automobile) or the right to earn a living and pursue calling, occupation and trade of common right not located at one’s own address or abode, (3) the right to contract or not contract with insurance companies if one is not involved in Uber, DoorDash or trucking/transportation/logistics field and not part of any financial or business or corporate concern, and (4) right to a hearing and due process before revocation of a state privilege available to every law-abiding citizen.

DOR tells petitioner that if he doesn’t enter into contract to buy insurance, he has alternatives. (1) Give Cmsr. Gerregano a $65,000 cash payment, (2) buy a corporate surety bond that petitioner puts into evidence is not available in the market (Affidavit of inability to purchase surety bond), (3) stop using the public road for any purpose in an automobile or motor vehicle, or (3) face criminal prosecution from respondents’ agents and privies for enjoying use of private property, his 2000 Honda Odyssey minivan used apart from any state privilege.

The right to have and use property apart from privilege is constitutionally guaranteed, as noted in the privilege cases. See Phillips v. Lewis, 3 Shannon’s cases 230, 1877. Privilege law is upon acts of commercial nature for private profit and gain affecting the public interest, which distinction respondent vigorously denies.

The right to contract – or to not contract. This right is constitutionally guaranteed. No authority exists for a department or commissioner to criminalize use of the ordinary means of the day on the public right of way in exercise of individual rights of ingress and egress, and force the public into a contract with insurance or bonding agencies.

Free use of the people’s roads must be recognized, for by free use are many rights enjoyed. For example, press rights (Tenn. Const. Art 1 § 19). Obstructing automobile use quashes this communication enjoyment.

The right of ingress and egress from one’s place is constitutionally protected, as noted in 13 Tennessee court cases cited to respondent. Exercise of that right allows pleasure and comfort of a host of others, as follows:

Free exercise of rights of conscience in religion (Tenn. const. art 1, § 3), free assembly (Tenn. const. art. 1 § 23), right to open courts and travel there (Tenn. const. art. 1 § 17), suffrage and elections (Tenn. const. art 1 § 5), freehold, liberties or privileges, and right to earn living in calling of common right (Tenn. const. art. 1 § 7 and 8), right to property and contract (Tenn. const. art. 1 § 21) and due process (Tenn. const. art. 1 § 8).

No authority exists under the Tennessee constitution for any department or official to use extortion to forbid insurance industry noncustomers from using roads thrown open for public travel or use free of charge. T.C.A. § 67-5-204

Respondent overthrow of law denies petitioner a hearing before revocation in violation of his due process rights to a hearing before the axe falls. Hearings under TFRL are at T.C.A. § 55-12-103 in DOSHS. Beazley v. Armour, 420 F. Supp. 503, 506, 507, 509 (M.D. Tenn. 1976). Except in emergency situations, due process requires that when state seeks to terminate interest such as driver's license it must afford notice and opportunity for hearing appropriate to the nature of case before termination becomes effective. Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535, 91 S. Ct. 1586, 29 L. Ed. 2d 90 (1971).

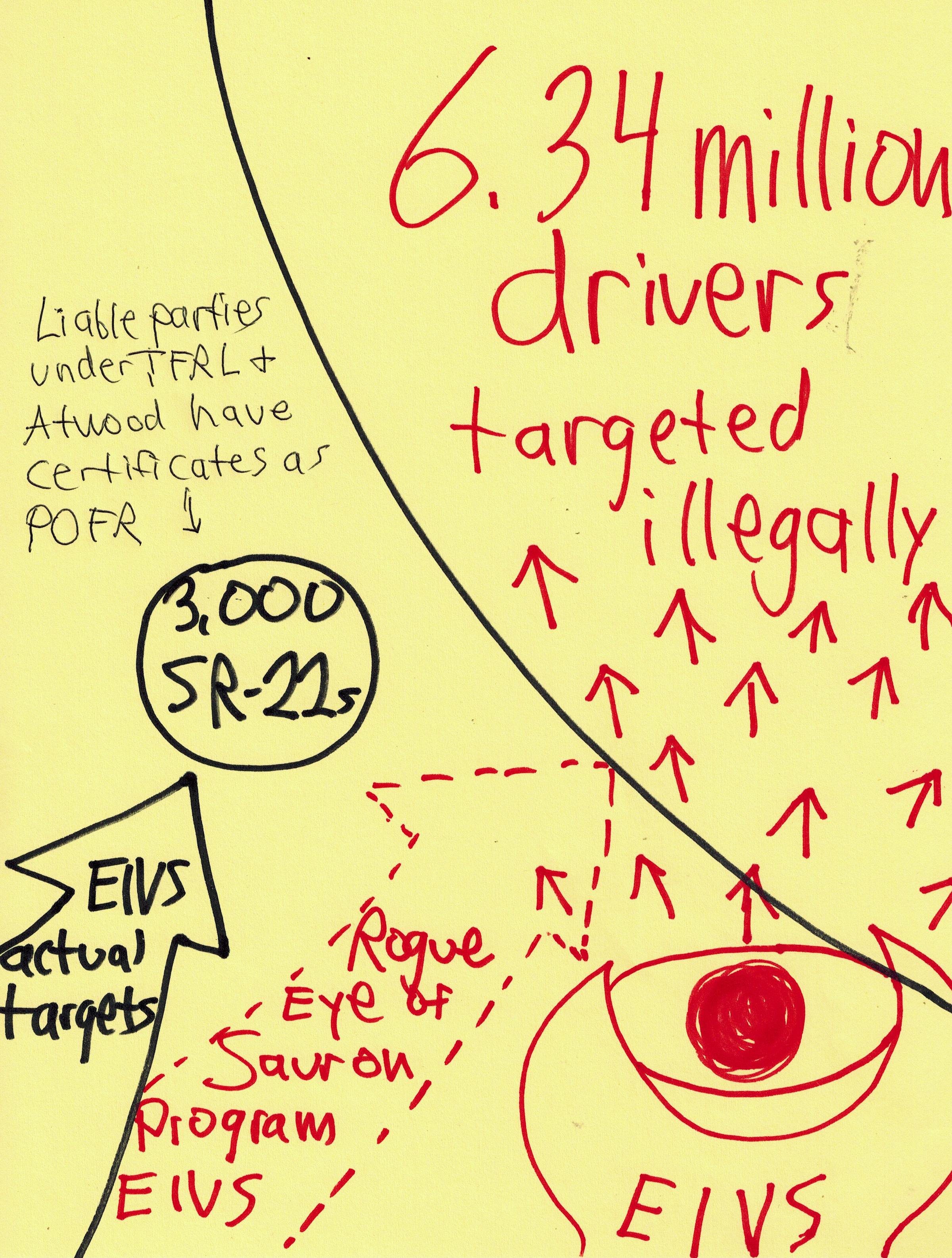

That five of every six registrants are rich enough to buy auto insurance doesn’t make respondents’ “Eye of Sauron” program less unconstitutional; that the poor suffer doesn’t make it more. Obstruction against the function of the law, however, reasonably afflicts the poor the most, as they have few means of dealing with sky-high premiums, criminal accusations under § 139, hauled-off autos and vehicles, tow company storage fees, and, if jailed, bail bond fees, sheriff department cash card-on-exit skims and loss of work hours.

Respondent and its privies count on crime-preventing or conservator of the peace powers to have criminally charged or arrest on sight all people whose evidences of commercial roadway use — registration tags and driver licenses — are not in good standing (revoked, suspended, expired). Police power practice in Tennessee operates effectively as a bill of attainder against private activity on the public road that does not affect the public interest and is not that for which the privilege is required.