Complaint v. ‘Coty Coyote’ targets DA attack on church work, 3 other protected rights

Radio journalist files 42-page brief, demands TN lawyer ethics panel suspend Wamp for abrogating press, religion, free assembly, open courts

CHATTANOOGA, Tenn., Wednesday, Sept. 11, 2024 — My grievance against Coty Wamp seeks prosecution by the board of professional responsibility, or BPR, for her oppressive acts to block coverage of her vindictive prosecutoion of “2A Ray” Rzeplinski and to forbid Christian mercies upon a woman falsely jailed under a corrupt county arrest warrant policy.

Miss Wamp is threatening to prosecute this reporter if he does anything more than talk about law — she promises to prosecute him for helping any abused person under illegal and vile practices in Hamilton County that put people in jail without probable cause and apart from a lawful warrant.

The general assembly can impeach Miss Wamp for her abuses. But that is a far off prospect. Ouster is not possible since she is a state officvial. The best option for Chattanoogans aggrieved by her misdoings and malfeasance is to complain to those in authority over her license, namely the BPR.

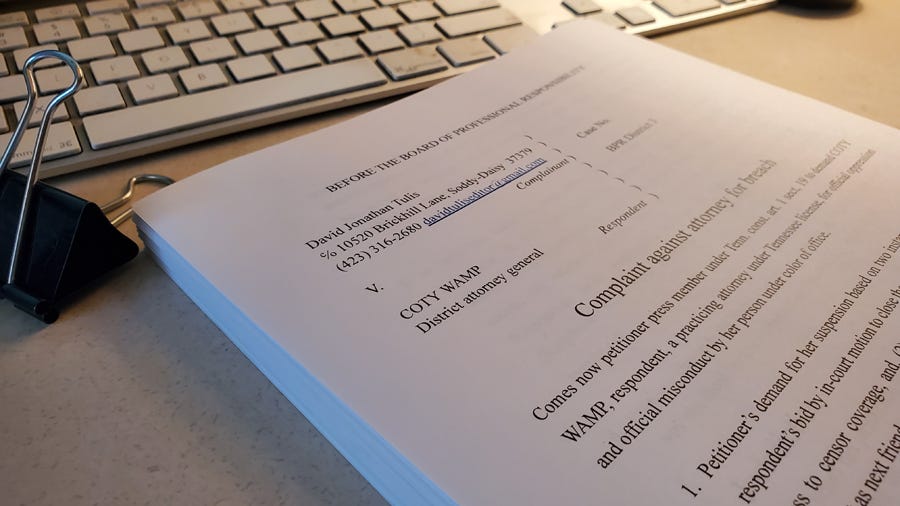

OFFICIAL COMPLAINT

Comes now petitioner press member under Tenn. const. art. 1 sect, 19 to demand COTY WAMP, respondent, a practicing attorney under Tennessee license, for official oppression and official misconduct by her person under color of office.

Petitioner’s demand for her suspension based on two instances of misconduct. (1) respondent’s bid by in-court motion to close the courts building to a member of the press to censor coverage, and, (2) her attack on his religious ministry of legal combat as next friend serving a falsely arrested citizen.

Her suit against petitioner arising out of a motion in State v. Ray Rzeplinski, case No. 31674, to bar relator from the Hamilton County courts building at 600 Market St., Chattanooga, singles him out with malice and prejudice and abrogates the press function “to examine the proceedings” to hold government officials accountable for their acts, guaranteed in the state constitution at art. 1, sect. 19, be abrogated. For the press to function, citizens have a guarantee in Tenn. const. Art. 1, sect. 17, “[T]hat all courts shall be open,” enjoyment of which right, too, respondent would abrogate. The second instance of malfeasance under color of law is in the context of State v. Tamela Grace Massengale, which defendant has an absolute right to counsel of her choice, and her choice of relator as counsel under her power of attorney and his acceptance of this office was, according to respondent, the unlicensed practice of law (“UPL”) at Tenn. code ann. § 23-3-101 et seq, a crime.

For immediate release — Reporter demands Wamp suspension

In these two instances, respondent’s actions under color of office attacks the enjoyment of four constitutionally guaranteed, inherent, unalienable and God-given rights protected by State of Tennessee, these being (1) press, (2) open courts, (3) religious practice, and (4) right of remonstrance and address. Respondent holds petitioner’s exercise of these rights require abatement (Rzeplinski case press coverage) or a suppression as crime (Massengale assistance).

Petitioner demands the board examine relevant law so respondent can show cause why she should not be suspended or disbarred for breach of law.

Jurisdiction

The board has jurisdiction to hear this matter pursuant to Sup.Ct.Rules, Rule 9, § 4, creating the Board of Professional Responsibility of the Supreme Court of Tennessee “[t]o consider and investigate any alleged ground for discipline or alleged incapacity of any attorney called to its attention.” Attorney acting as publicly elected district attorney general nevertheless remains subject to the code of professional responsibility, and may be suspended or disbarred for misconduct, even though exclusive method for removal from office is impeachment. Sup.Ct.Rules, Rule 8, Code of Prof.Resp., Canon 1 et seq.; Sup.Ct.Rules, Rule 9, § 1 et seq. Ramsey v. Board of Professional Responsibility of Supreme Court of Tennessee, 1989, 771 S.W.2d 116, certiorari denied 110 S.Ct. 278, 493 U.S. 917, 107 L.Ed.2d 258.

Parties

Petitioner runs 107.5 FM radio station and others in the local Copperhead Radio Network in Chattanooga. He reports on the airwaves, at TNtrafficticket.US and on DavidTulis.Substack.com under guarantees of the federal 1st amendment and Tenn. const. Art. 1, sect. 19, “[t]hat the printing press shall be free to every person.”

Respondent Coty Wamp is elected district attorney general of the 11th judicial district and a public servant. She works in an office at 600 Market St., Suite 310, Chattanooga, Tenn. 37402.

Factual background

Relator complainant has been a member of the press in Chattanooga most of his life, having worked 24 years as a copy editor at the Chattanooga Times Free Press and for 13 years as commentator and reporter in radio, first at Copperhead Radio, then NoogaRadio Network and now at 107.5 FM and the Copperhead Radio Network.

He has reported extensively on criminal cases State v. Rzeplinski and State v. Massengale.

The Takeaway ——————————————————-

➤ Lawyering is a privilege, and privilege law controls many public-facing occupations

➤ For an activity to be subect to privilege law (practicing law, driving car) there must be payment

➤ A complaint vs. lawyer need not argue law, only present facts; here, I do both

➤ Many rights coalesce around open meetings, right to assemble

Respondent has used her office twice in exercise of her law enforcement authority vis a vis relator in his exercise of constitutionally guaranteed rights, as follows.

1. Rzeplinski case coverage

The Hamilton County criminal court, the state and Rzeplinski parties set July 29, 2024, a Monday, as trial date in State v. Raymond Rzeplinski, division II, No. 316374.

Complainant has been covering the case – the only press outlet eyeing what his reporter called a vindictive prosecution, with petitioner’s coverage suggesting the case is ripe for jury nullification to thwart the routine operation of what one legal historian calls America’s “conviction factory.” (1) Respondent charged defendant as being a felon in possession of firearms.

On July 25, 2024, the Thursday before trial, respondent files State’s motion regarding attempts at jury nullification. EXHIBIT No. 1. Respondent motion to censor. It demands the court order relator be barred not just from the Rzeplinski trial courtroom, but the entirety of the publicly accessible areas of the court’s building.

The grounds of the demand are that reporting and commentary in favor of jury power and jury nullification has “tainted the jury pool” and that such expression implies he would be disruptive as a citizen listening in at the trial or as a reporter under Rule 30 media rules were he to use press equipment such as laptop, camera and audio recorder to gather material for his report.

The injunction suit against relator Tulis is e-mailed to the court Thursday evening, a copy is served on Ben McGowan, Mr. Rzeplinski’s attorney, Respondent omits service or notice to petitioner.

Complainant learns about her filing that evening and prepares a defense. Next day, July 26, 2024, Friday, around noon, he files with the court as relator in the name of the state Objection to motion to censor, demand for sanctions, demanding a hearing.

Monday morning at roughly 8:45, the bailiff hands petitioner the court’s answer, an order denying motion to censor on free press and open courts grounds.

The court readily accepts relator’s presence during Rzeplinski proceedings as member of the public, granting his timely filed Rule 30 request for use of his laptop and other devices as member of the press.

The court says that the dispute between respondent and state of Tennessee on relation over respondent’s motion of threat against his rights will be held “in abeyance” until after the trial.

2. Attack on remonstrance & religion rights, ‘next friend’ role

Tamela Grace Massengale is a crime victim falsely imprisoned and arrested under an arrest warrant policy of Hamilton County’s chief magistrate, Lorrie Miller. Respondent criminally prosecuted Mrs. Massengale in case no(s). l94l9l2 and 1941913 in the general sessions court before dropping the case, which is expunged. The arrest and jailing of Mrs. Massengale are without probable cause.

Tenn. const. Art. 1, sect. 17, requires “that all courts shall be open.” The door to the Hamilton County magistrate’s office, however, is closed and locked to the public in breach of this provision. The magistrate bars members of the public from drafting and submitting under oath before the magistrate warrants for arrest, which warrant the magistrate, who is supposed to be a neutral third party, accepts or rejects.

The locked door to the magistrate’s office is not a bar to all. The county’s program of “doggie door warrants” allows police officers and deputies instant access to the magistrate through, as it were, a small door near the floor, mandating that only government employees may enter and that they must necessarily proffer and obtain hearsay-only arrest warrants.

Hearsay is accepted in an arrest warrant, but is by no means required. The policy denies magistrate access to first-hand facts witnesses and crime victims with first-hand knowledge of an offense. The requirement that only hearsay-only warrants issue is a departure from law.

Press member complainant has reported on this unconstitutional program in detail. In a Dec. 26, 2023, letter he demands Mrs. Miller the basis for her program. See p. 19, EXHIBIT No. 4, Tulis Dec. 26, 2023, demand letter to magistrate Miller

Relator sends this letter to the county’s three criminal court judges. Radio news reporting on NoogaRadio Network, extensive coverage at TNtrafficticket.us, oral demands for reform before the county commission, detailed written legal notice to the commission, and relator demands before criminal court judges, including Hamilton County criminal court Judge Boyd Patterson, bring the public no relief from the due process violations that thrive under Magistrate Miller’s doggie-door warrants.

Relator’s concern is not just on behalf of members of the public, but for benefit of public servants. As parties are involved in an illegal program, they are in their estates and properties personally liable for harm caused upon such as Mrs. Massengale. Exposing municipal parties to personal liability is not according to law and is not good public policy for Hamilton County.

The office of magistrate is at the center of much police power abuse in Hamilton County. Complainant has reported doggie door arrest warrant policy has injured truck driver Michael James, pallet recycler Shameca Burt (108 days in Silverdale), a rape victim identified to the courts, and Mrs. Massengale. Officers have instant access to the magistrate for creation of arrest warrants based on one-side-only hearsay, unsworn by a purported victim, which harm is that created upon Mrs. Massengale.

Doggie door warrants degrade the quality of cases handled by public defenders and district attorney lawyers, and are a manifest injustice that should shock the conscience of any public servant hearing of the problem.

Mrs. Massengale intends to challenge this system, which she insists is proper to her defense in her criminal case and a sure benefit to the larger public. She pleads petitioner help her bring an end to the mass injury policy accepted as proper status quo by all county public officials, with no exception known to relator or Mrs. Massengale. She asks the injury done her be converted into a restorative and balm upon the people’s injured rights.

Mrs. Massengale is a crime victim in a Venmo refund scam. The arrest warrant upon her is premised on a phone call made to Chattanooga police department employee Brandi Siler, a policewoman, who uses the magistrate’s office “doggie door” to present an unsworn hearsay-only draft arrest warrant and charging instrument to the magistrate.

Magistrate Blake Murchison accepts Ms. Siler’s draft as an arrest warrant. He makes no determination that Ms. Siler investigated Mrs. Massengale’s side of the story, or finds no fault in learning that Ofcr. Siler hasn’t.

Mrs. Massengale’s arrest, jailing and prosecution, lacking probable cause, is void from inception.

On her request, while State v. Massengale is pending in county sessions court, complainant swings into action on behalf of state of Tennessee on relation under religious motivation and purpose.

Petitioner in role as next friend files Affidavit and remonstrance in re Tamela Grace Massengale false imprisonment & false arrest; Petition for writ of certiorari, seeking to remove the case from the court of Judge Larry Ables so that the cause might be dismissed ministerially in a court of record, and reform imposed.

Criminal has adjudicative and supervisory authority to order a straightening up of the Hamilton County magistracy into its constitutional posture under Tenn. Code Ann. § § 40-6-203, 204, 205 and Tenn. R.Crim Proc. Rules 3 and 4, relator contends.

In e-mail serving respondent, petitioner states, “Mrs. Massengale is in Judge Able’s court Monday morning. I don’t want it dismissed, I want it elevated so Judge Dunn or one of the other two judges will have unquestioned jurisdiction over it even though it is void as a matter of law. I filed notice with sessions about the filing, enclosing a copy. A clerk said he would take it immediately to Judge Ables.”

On July 10, 2024, petitioner joins with Mrs. Massengale in her initial appearance before Judge Ables. A published transcript of the hearing indicates the court rejects Mrs. Mssengale’s choice of counsel, as she expresses it in alignment with her affidavit of appointment.

The 6th amendment says “In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right *** to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defense.” The Tennessee constitution guarantees in art. 1, sect. 9, “That in all criminal prosecutions, the accused hath the right to be heard by himself and his counsel” (emphasis added).

The court is visibly angry on grounds that counsel of choice means only attorney of choice, and no person other than a licensee in privileged business under the Tennessee supreme court may speak with or for the accused or serve her.

The sessions court rejects petitioner’s claim of Christian ministerial and advocacy service on Mrs. Massengale’s part. As witnessed by three assistant district attorneys serving respondent, the court berates petitioner as a lawbreaker subject to criminal prosecution under the unlicensed practice of law statute. The court denies petitioner’s presentation of his religious premise, and says that not receiving valuable consideration is irrelevant because he drafted legal papers and stands in presence of the court with the accused. Drafting, filing, standing to address a court are enough, he says, to constitute unlicensed practice of law, regardless of the lack of valuable consideration. (3)

The sessions court assigns Mike Little as public defender. He files a motion on Mrs. Massengale’s behalf for the court to strike Mrs. Massengale’s remonstrance and petition and defeat her intentions. See EXHIBIT No. 1 p. 30, public defender’s motion to strike.

On June 4, 2024, the Hamilton County criminal court Judge Amanda Dunn issues Order of dismissal as to petition for writ of certiorari on grounds of standing.

Respondent drops the charges against Mrs. Massengale. Refusal to prosecute indicates its defective origins, admits it to have been a false imprisonment and false arrest, an actionable tort by officer Siler and others, lacking probable cause, lacking any sworn statement by the purported crime victim, and an injury to the peace and tranquility of the state.

A criminal court judge inks the expungement order for the Massengale case.

Respondent sends relator a letter dated May 6, 2024, alleging that he is involved in unlicensed practice of law. The DA “does not plan on charging you” for assisting Mrs. Massengale but, respondent says, “future violations of this statute on your part will lead to criminal charges.”

Respondent’s premise is that the UPL law forbids any advocacy, remonstrance or address before the judicial branch of government, or before any of its public servants, and that only paid licensed attorneys exercising a state privilege as a for-profit business may speak to courts and judges. The letter says relator is performing activities that can be done only under state privilege and only by law advocates so licensed to draft legal documents and file papers and to speak with and for a defendant before a court.

Respondent says she will criminally prosecute relator if he attempts to assist any other person, whom she effectively states cannot have counsel of that person’s choice if that person happens to light upon relator as sagacious proponent of due process rights and likely to assist that person in defense of local policing for profit or other abuse.

Second, you claim that you are not operating a law business or practice. This would indeed indicate that you would not be charged under the “law business” portion of Tenn. Code Ann. $ 23-3-103(a). However, if you refer to the above-quoted statutes, you will see that the drawing up and filing of your “Notice of petition for petition for writ of certiorari” qualifies a “drawing of papers, pleadings, or documents” on behalf of another individual.” Furthermore, you have held yourself out repeatedly as “representing” Tamela Grace Massengale, which is indicative of your unauthorized practice of law. This claim of representation has been witnessed by members of our office, by the Court, and in writing on your website.

Wamp letter, pp. 2, 3

The implication of this statement — “would not be charged under the ‘law business’ portion of Tenn. Code Ann. § 23-3-103(a)” — is that respondent has authority to prosecute a person for UPL apart from the essential element of valuable consideration.

Legal authorities

The legal authorities involved in this complaint include the rules of professional responsibility, laws pertaining to the rights of press, the right to open courts, the right (and duty) of free assembly for purpose of remonstrance and address, and the right of religion, all of which respondent challenges in her office of trust as district attorney general and as licensee subject to the board and the supreme court.

Rules of professional conduct

The supreme court’s rules governing the privilege of law practice are Rule 8. This case invokes Rule 3.3 regarding allegations of false statements about law. “(a) A lawyer shall not knowingly: (1) make a false statement of fact or law to a tribunal; or (2) fail to disclose to the tribunal legal authority in the controlling jurisdiction known to the lawyer to be directly adverse to the position of the client and not disclosed by opposing counsel.” A lawyer is forbidden “from making misleading legal argument.” which is one “based on a knowingly false representation of law [that] constitutes dishonesty toward the tribunal. A lawyer is not required to make a disinterested exposition of the law, but must recognize the existence of pertinent legal authorities. Furthermore, as stated in paragraph (a)(2), an advocate has a duty to disclose directly adverse authority in the controlling jurisdiction that has not been disclosed by the opposing party. The underlying concept is that legal argument is a discussion seeking to determine the legal premises properly applicable to the case.”

Rule 1.2 prohibits an attorney aiding in crime, and impliedly committing crime: “(d) A lawyer shall not counsel a client to engage, or assist a client, in conduct that the lawyer knows or reasonably should know is criminal or fraudulent[.]”

Misconduct is prohibited. “It is professional misconduct for a lawyer to: (a) violate or attempt to violate the Rules of Professional Conduct, knowingly assist or induce another to do so, or do so through the acts of another; (b) commit a criminal act that reflects adversely on the lawyer's honesty, trustworthiness, or fitness as a lawyer in other respects; (c) engage in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit, or misrepresentation; (d) engage in conduct that is prejudicial to the administration of justice.” Rule 8.4.

The fact narrative of this case touches on systemic judicial abuses in Hamilton County, particularly as regards the poor and how built-in violations of due process against them as reported by press member complainant “undermine public confidence in the administration of justice,” quoting from court comment on rule 8.2.

From the preamble of the supreme court’s rules of professional responsibility, “[7] As a public citizen, a lawyer should seek improvement of the law, access to the legal system, the administration of justice, and the quality of service rendered by the legal profession. *** [A] lawyer should cultivate knowledge of the law beyond its use for clients, employ that knowledge in reform of the law, and work to strengthen legal education” and “should further the public's understanding of and confidence in the rule of law and the justice system because legal institutions in a constitutional democracy depend on popular participation and support to maintain their authority. A lawyer should be mindful of deficiencies in the administration of justice and of the fact that the poor, and sometimes persons who are not poor, cannot afford adequate legal assistance.” A licensee “should help the bar regulate itself in the public interest.”

Oppression law

Complainant highlights the official oppression statute at § 39-16-403 to bring into view “[a] public servant acting under color of office or employment [who] commits an offense who: (1) Intentionally subjects another to mistreatment or to arrest, detention, stop, frisk, halt, search, seizure, dispossession, assessment or lien when the public servant knows the conduct is unlawful; or (2) Intentionally denies or impedes another in the exercise or enjoyment of any right, privilege, power or immunity, when the public servant knows the conduct is unlawful” (emphasis added).

Privilege law

Respondent accuses petitioner of acts forbidden if not done under privilege. Privilege is required in operation of a business subject to state requirement. “The tax here in suit was not a tax levied upon complainant’s water, but was a privilege tax levied upon the business of selling the water.” Seven Springs Water Co. v. Kennedy, 156 Tenn. 1, 299 S.W. 792, 5 (1927) (emphasis added).

However, selling legal filings and holding forth as one who sells legal filings and makes court appearances require a tax be paid for the privilege of becoming a state-licensed attorney. If one is entering into a business, the first act of that business is subject to privilege, if indeed business is the intention of the actor.

It follows that the Legislature cannot tax a single act, per se, as a privilege, inasmuch as such act, in the nature of things, cannot, in and of itself, constitute a business, avocation, or pursuit. Hence it is a matter of importance “whether they make a business of it, or not,” since if they do not, there is no privilege to be subjected to taxation. This portion of the statute must therefore be held nugatory.

Yet the proof of a single act which is characteristic of any of the privileges created by the Legislature is by no means unimportant, because evidence of such act necessarily casts the burden of proof upon the defendant to show that he was not in fact exercising the privilege; that is, engaged in a business or occupation of the kind indicated by the act. The doing of such act makes a prima facie case against him.

Indeed, the doing of a single act may itself be conclusive evidence of the fact of one's entry upon a given business, as where a merchant, after having procured his goods and placed them in his store, opens his doors and makes one sale, or where an abstract company, after having prepared its books of reference and procured its office, issued one abstract, or where a photographer, after having prepared himself for business, takes one picture, or an auctioneer sells, as such, one article, or a real estate agent makes one sale, and so on.

In entering upon a business there is a union of act and intention — the purpose to enter thereon, and the consummation of that purpose by making a beginning, performing the initial act.

Trentham v. Moore, 111 Tenn. 346, 76 S.W. 904, 904 (1903) (emphases added)

Privilege is a calling, occupation or vocation that affects the public interest, and requires a license, having always a first sale, as the Trentham court notes. The constitution provides only one other way for taxation in Tennessee. Ad valorem. With privilege, the state’s authority is recognized in Tenn. const. art. 2, sect. 28. “The Legislature shall have power to tax merchants, peddlers, and privileges, in such manner as they may from time to time direct, and the Legislature may levy a gross receipts tax on merchants and businesses in lieu of ad valorem taxes on the inventories of merchandise held by such merchants and businesses for sale or exchange.”

In the Seven Springs Water case, “Complainant was a farmer near Knoxville and had a spring of water on his place. The water had no mineral or medicinal properties of value, but seems to have been a pure and palatable drinking water. Complainant, therefore, began putting the water in suitable containers and selling and delivering it to customers in different parts of Knox County.” The court says that while the water at issue comes from the soil, and might otherwise not be taxable, the mineral water dealers law “clearly imposes the tax upon one engaged in the business of selling ‘either distilled water or water from springs or well or mineral water,'” Id., Seven Springs Water at 6.

The cases make distinction between property and activity subject to excise or privilege tax. Owning a stallion is not taxable, nor requires the privilege. But “[keeping] a stallion or jack, for mares” is. That is selling reproductive services for profit, requiring an excise tax be paid. Cate v. State, 3 Sneed, 121. The state may impose a fee on dogs under police powers, “to protect the safety of the people and of property from their offensive and destructive propensities”; but it can’t raise revenue by converting ownership into a privilege where objects are taxed merely or existing. State v. Erwin, 139 Tenn. 341, 200 S.W. 973, 973–74 (1918).

Case law recognizes no distinction between a privilege tax and an excise tax. See Bank of Commerce & Trust Co. v. Senter, 260 S.W. 144, 148 (Tenn. 1924) (“Whether the tax be characterized in the statute as a privilege tax or an excise tax is but a choice of synonymous words, for an excise tax is an indirect or privilege tax.”); American Airways, Inc. v. Wallace, 57 F.2d 877, 880 (M.D. Tenn. 1937) (“The terms ‘excise’ tax and ‘privilege’ tax are synonymous and the two are often used interchangeably.”); see also 71 AM JUR. 2d State and Local Taxation §24, (“The term ‘excise tax’ is synonymous with ‘privilege tax,’ and the two have been used interchangeably. Whether a tax is characterized in the statute imposing it as a privilege tax or an excise tax is merely a choice of synonymous words, for an excise tax is a privilege tax.”) “It cannot be denied that the Legislature can name any privilege a taxable privilege and tax it by means other than an income tax, but the Legislature cannot name something to be a taxable privilege unless it is first a privilege.” Jack Cole Co. v. MacFarland, 337 S.W.2d 453, 455 (Tenn. 1960). Waters v. Chumley, Tenn: Court of Appeals 2007 No.E2006-02225-COA-R3-CV.

“PRIVILEGE. A particular and peculiar benefit or advantage enjoyed by a person, company, or class, beyond the common advantages of other citizens,” says Black’s Law Dictionary, 4th ed. “An exceptional or extraordinary power or exemption. A right, power, franchise, or immunity held by a person or class, against or beyond the course of the law. [citations omitted] *** An exemption from some burden or attendance, with which certain persons are indulged, from a supposition of law that the stations they fill, or the offices they are engaged in, are such as require all their time and care, and that, therefore, without this indulgence, it would be impracticable to execute such offices to that advantage which the public good requires.*** A peculiar advantage, exemption, or immunity.”

Trentham v. Moore lists 21 privilege cases, the leading among them being Phillips v. Lewis 3 Shann. Cas. 230 (1877) showing under privilege the levy is not upon property, but for-profit activity “directed to a profit to be made off the general public.”

P. 238, 239 The language is that hereafter the keeping of dogs shall be a privilege which shall be taxed as follows, etc. In this view of the question, the real point presented is whether the simple ownership of property of any kind can be declared by the legislature a privilege, and taxed as such, for if it can be done in the case of a dog, it may be done in the case of a horse, or any other species of property. It is clear this is what is done by this statute, except that it has gone even further, and taxed a party who shall harbor or give shelter to a cur on his premises. This latter privilege, we take it, is one that will not be much sought after, but to the main question. It is evident the words, “keeping of dogs,” in the statute mean simply ownership *** [.]

***

P. 240 “Merchants, peddlers and privileges,” are the defined objects of taxation in the latter clause of the section. It is certain the merchant is not taxed except by reason of his occupation, and in order to follow or pursue this occupation – one of profit – in which it may be generally assumed capital, skill, labor, and talent are the elements of success, and are called into play by its pursuit. This pursuit or occupation is taxed, not as property, but as an occupation. Another element of this occupation is, that its object and pursuit is directed to a profit to be made off the general public, the merchant having a relation, by reason of his occupation, to the whole community in which he may do business, by reason of which he reaps, or is assumed to reap, the larger profit by drawing upon or getting the benefit of the resources of those surrounding him. The same idea is involved in the case of the peddler, who may range over a whole county by virtue of his license. His is an occupation of like character, a peculiar use of his capital, varied only in some of its incidents.

These occupations are taxed as such, and not on the ad valorem principle. So we take it the word privilege was intended to designate a larger, perhaps an indefinite class of objects, having the same or similar elements in them, distinguishing them from property, and these objects were to be defined by the legislature and taxed in like manner as might be deemed proper. But the essential element distinguishing the two modes of taxation was intended to be kept up. That is the difference between property and occupation or business dealing with and reaping profit from the general public, or peculiar and public uses of property by which a profit is derived from the community. ***

Page 241. The case of Marbury v. Tarver, 1 Hum. 94, was under the Act of 1835 *** prohibiting the keeping, or rather, using the jackass for profit in the propagation of stock. Here it is clear it was the keeping of the animal, and using him for profit to be derived from the public in a particular manner, that was declared to be a privilege and taxed as such. It is not a tax on the jack, or for owning him or harboring him as the case before us, but a tax upon the particular public use to which he is put, that makes the element of privilege in that case.

P. 243 We may concede *** that an actual license issued to the party is not an essential feature of a privilege, but is only the evidence of this grant of the right to follow the “occupation or pursuit,” and the usual and perhaps universal incident to such grant, or that a tax receipt is, or even may be the evidence of the grant. Still, the thing declared to be a privilege is the occupation, the license but the incident to its engagement, described by statute, assuming, however, the license in one form or the other is to be had. We think it would be impossible to hold, in any accurate sense, that a man could only be entitled to hold and possess his property, paid for with his money and earned by his labor, upon the condition of obtaining a license, either from the county clerk, or a tax collector. His right is indefeasible under the constitution of the state. He can only be deprived of it by due process of law, or the law of the land as hereinafter explained.

P.244 “[T]he tax is on the occupation, avocation, or calling, it being one in which a profit is supposed to be derived, by its exercise, from the general public.

Phillips v. Lewis, 3 Shann. Cas. 230 (1877) (emphases added). EXHIBIT No. 8. Copy of case. (4)

Courts belong to the people. A law business making private profit in the use of courtrooms and court buildings is subject to privilege, just as a trucking company is able to use the public rights of way that belong to the people — but only under privilege, because its private profit affects the public interest.

The business of using the public highways for profit, earned by transporting persons and property for hire, has been definitely excluded from the category of private or personal rights arising from citizenship. Recent decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States have determined certain fundamental principles concerning the use of the highways. One is “that the primary use of the state highways is the use for private purposes; that no person is entitled to use the highways for gain as a matter of common right.” Hoover Motor Express Co. v. Fort, 167 Tenn. 628, 72 S.W. (2d) 1052, 1055. The statement and definition of the terms and conditions upon which a privilege, not a matter of common right, may be exercised is, we think, within the declared purpose of regulation and does not amount to prohibition. In such a case the prevention of an unauthorized exercise of the privilege is clearly implied in the statement of the purpose to regulate it.

The statute under consideration is a comprehensive regulation of the use of the state highway system by both common carriers and contract carriers. It is designed, as declared in section 21, to promote and preserve economically sound transportation, to regulate the burden of use to which the highways may be subjected, to protect the safety of the traveling public, and to protect the property of the state in the highways from unreasonable, improper, or excessive use.

State v. Harris, 168 Tenn. 159, 76 S.W.2d 324, 325 (1934)

Roads and highways are free for use of the traveling public, for pleasure, for necessities and for enjoyment of rights. “[N]o person [corporation] is entitled to use the highways for gain.” The same for the courts.

State law prohibits the unlicensed practice of law, or the exercise of a law business in commerce outside state privilege. The law occupation and business are property of state of Tennessee. “No person shall engage in the practice of law or do law business, or both, as defined in § 23-3-101, unless the person has been duly licensed and while the person's license is in full force and effect, nor shall any association or corporation engage in the practice of the law or do law business, or both.” An essential element of a law practice or business is drafting court filings or giving legal counsel for pay.

“Law business” means the advising or counseling for valuable consideration of any person as to any secular law, the drawing or the procuring of or assisting in the drawing for valuable consideration of any paper, document or instrument affecting or relating to secular rights, the doing of any act for valuable consideration in a representative capacity, obtaining or tending to secure for any person any property or property rights whatsoever, or the soliciting of clients directly or indirectly to provide such services;

Tenn. Code Ann. § 23-3-101 (emphases added)

Respondent accuses petitioner of making a living and pursuing a livelihood and occupation buying and selling legal service as lawyer and attorney when he acts as next friend to Mrs. Massengale. He is alleged to be treading upon the state’s ownership of the materiel of petition, pleading, requesting, motioning to public servants in the third branch of Tennessee government, the judiciary.

Lawyers and attorneys are privileged to engage in these activities because they earn “valuable consideration” in courtrooms that belong to the people of Tennessee. They have no right to earn their livings upon the assets, property and tax-maintained infrastructure of the public.

Valuable consideration is an essential element of the crime of unlicensed practice of law.

Religious, petition protections

Whether petitioner’s activities under religious motivation and protection violates the privilege requirement is a matter of law if it is stipulated he serves oppressed people gratis, under armature of religion with no evidence of valuable consideration received.

Religious activity enjoys protection under law. Petitioner is bound by religious training and “belief in a relation to a Supreme Being involving duties superior to those arising from any human relation” United States v. Seeger, 380 U.S. 163, 173, 85 S. Ct. 850, 858, 13 L. Ed. 2d 733 (1965). Religious practice and motivation are protected, whereas “essentially political, sociological or economic considerations” or a “merely personal moral code” are not.

The law that binds petitioner’s next friend conscience arises from the institutes of the Christian religion and the institutes of biblical law:

“Woe to those who make unjust laws, to those who issue oppressive decrees, to deprive the poor of their rights and withhold justice from the oppressed of my people, making widows their prey and robbing the fatherless.” – Isaiah 10:1, 2

“Woe to those who plan iniquity, to those who plot evil on their beds! At morning’s light they carry it out because it is in their power to do it. They covet fields and seize them, and houses, and take them. They defraud people of their homes, they rob them of their inheritance.” Micah 2:1, 2

“You shall not follow a crowd to do evil; nor shall you testify in a dispute so as to turn aside after many to pervert justice.” Exodus 23:2.

“Happy is he *** who executes justice for the oppressed, who gives food to the hungry. The LORD gives freedom to the prisoners. *** The LORD watches over strangers; he relieves the fatherless and widow; but the way of the wicked he turns upside down.” Ps 146:5, 7, 9.

“To crush under one's feet All the prisoners of the earth, To turn aside the justice due a man Before the face of the Most High, Or subvert a man in his cause -- The Lord does not approve.” Lamentations 3:35, 36.

Amos warns that God watches out for people who are the victims of injustice -- the abuse of law or privilege by the great against the lesser in the city. “For I know your manifold transgressions And your mighty sins: Afflicting the just and taking bribes; Diverting the poor from justice at the gate. Therefore the prudent keep silent at that time, For it is an evil time. Seek good and not evil, That you may live; So the Lord God of hosts will be with you, As you have spoken. Hate evil, love good; Establish justice in the gate.” Amos 3:12-14

“‘Cursed is the one who perverts the justice due the stranger, the fatherless, and widow.’ And all the people shall say, ‘Amen!’” Deut. 27.19.

“He will bring justice to the poor of the people; He will save the children of the needy, And will break in pieces the oppressor.” Psalm 72:4.

“He who despises his neighbor's sins: but he who has mercy on the poor, happy as he.” Prov. 14:21. “A true witness delivers souls, but a deceitful witness speaks lies.” Prov. 14:25. “A false witness will not go unpunished, and he who speaks lies will not escape.” Prov. 19:5. “Do not remove the ancient landmark, nor enter the fields of the fatherless; for their redeemer is mighty; He will plead their cause against you.” Prov. 23:10, 11. “Take away the dross from silver, and it will go to the silversmith for jewelry. Take away the wicked from before the king, and his throne will be established in righteousness.” Prov. 25:4, 5.

Petitioner arguably is a person “of law knowledge,” to use wording of Tenn. const. Art. 6 sect. 11 on judicial recusal. He uses what he knows for religious ends and for reform of public institutions that are part of God’s created order and subject to his law. The religious charge he acts upon is the same one that directs prophets such as Moses, Ezekiel, Jeremiah, John and Paul.

Respondent denies relator’s activity is enjoyment of religious conviction and liberty, and moves to abrogate it.

Jury tampering law

Respondent makes allegations about jury tampering. It is a Class A misdemeanor to “tamper with” or “taint” a juror, using terms from respondent. The act occurs when one “privately communicates with a juror with intent to influence the outcome of the proceeding on the basis of considerations other than those authorized by law” at Tenn. Code Ann. § 39-16-509. A member of the general public becomes a juror at the end of voir dire, when the body is empaneled and members sworn. Tenn. Code Ann. § 22-2-201(a)(2).

Next friend law

Respondent’s analysis on next friend status held by next friend in assisting Mrs. Massengale errs by citing case law irrelevant to those facing criminal prosecution in sessions or criminal court.

In protecting the “closed [union] shop” of the bar, as Justice Douglas puts it in Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483, 490, 89 S. Ct. 747, 751, 21 L. Ed. 2d 718 (1969), respondent implies that a defendant such as Mrs. Massengale cannot choose a next friend to speak with or for her because courts put limits on next friend role in cases involving post-conviction relief among death row inmates. She says the doctrine of next friend is asserted in cases of “a person who is incapacitated, mentally incompetent, or suffering from another such disability,” a doctrine “most often asserted during federal habeas corpus proceedings.”

Support David at GiveSendGo

Indeed, a party attempting to be next friend of someone in prison in a capital case faces high hurdles, must produce “evidence of an inmate's present mental incompetency by attaching to the petition affidavits, depositions, medical reports, or other credible evidence that contain specific factual allegations showing the inmate’s incompetence” Holton v. State, 201 S.W.3d 626 (Tenn. 2006), as amended on denial of reh’g (June 22, 2006). In a case cited by respondent, Whitmore v. Arkansas, 495 U.S. 149, 149, 110 S. Ct. 1717, 1720, 109 L. Ed. 2d 135 (1990), the death penalty case hinges “on the questions whether a third party has standing to challenge the validity of a death sentence imposed on a capital defendant who has elected to forgo his right of appeal.”

The constitutional guarantees for counsel of one’s choice may be constrained when pleaded by a death row inmate at the terminus of criminal litigation. The constitutions’ provisions are directed at requirements upon the state in launching criminal cases. Constitutional provisions focus intently on criminal case initiatory due process starting with search, seizure, probable cause and evidence culminating in trial by jury.

These and other cases cited in the Wamp letter to relator show no authority to limit a defendant in a misdemeanor preliminary hearing or a criminal trial from having a next friend speak with and for her and to draw up filings in lieu of a licensed attorney. The right in the next friend controversy is not relator’s right to be next friend. It is defendant’s right appoint her counsel, per federal 6th amendment and the 9th article in the Tennessee bill of rights.

Mrs. Massengale has right to have petitioner’s assistance so she can enjoy all her God-given, constitutionally guaranteed rights to due process, to address the court and to have her next friend address the court on equal footing “[t]hat in all criminal prosecutions, the accused hath the right to be heard by [herself] and [her] counsel” Tenn. const. Art 1, sect. 9.

With next friend speaking with and for her, and drafting and filing documents in her name under power of attorney, she’s able “to demand the nature and cause of the accusation against [her], and to have a copy thereof, to meet the witnesses face to face, to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in [her] favor, and in prosecutions by indictment or presentment, a speedy public trial, by an impartial jury of the County in which the crime shall have been committed, and shall not be compelled to give evidence against [herself]” Tenn. const. art. 1, sect. 9.

Whether it be Mrs. Massengale’s right to indictment by an unbiased grand jury or to obtain all exculpatory evidence from respondent’s office under the Brady rule, she has an absolute right not to lawyer of her choice, but counsel of her choice.

The Whitmore court sets forth a test on whether an inmate is disabled, allowing for a next friend. “[I]n keeping with the ancient tradition of the doctrine, we conclude that one necessary condition for ‘next friend’ standing in federal court is a showing by the proposed ‘next friend’ that the real party in interest is unable to litigate his own cause due to mental incapacity, lack of access to court, or other similar disability.” id., Whitmore at 165.

Mrs. Massengale is not at the end of the road in exercise of constitutional protections. She is at the beginning. Death row inmate next friend limitations do not apply to Mrs. Masengale. She has right to next friend aid, not as one “unable to litigate *** due to mental incapacity,” but as one with personal authority, power to consent and full presumption of innocence.

The Hamilton County criminal court under Judge Amanda Dunn is on record as acknowledging the sect. 9 right of a defendant to “be heard by himself and his counsel.” Ray Rzeplinski, represented though he was by attorney Ben McGowan, makes several addresses to the court per right.

Analysis

Miss Wamp’s motion asks that petitioner “be barred from entry to the courtroom during the proceedings of this trial. *** [T]he state is requesting that this court bar Mr. Tulis from the courthouse until the trial has concluded and the jury is released from service” (motion pp. 1, 5). Such bar would be in the nature of Hamilton County sheriff’s office deputies who would barricade the court building’s two entrances from entry by petitioner.

Such ban is intended to prevent him from “examin[ing] the proceedings of” a “branch *** of the government” and to “restrain the right thereof” so that “free communication of thoughts and opinions” not issue from relator as he wishes to “freely speak, write, and print” about the Rzeplinski case. Respondent would have the court issue an order (a law) executed by deputies and bailiffs against relator despite art. 1, sect. 19 decree that “no law shall ever be made to restrain the right” of the press.

This demand in State’s motion regarding attempts at jury nullification closes the courts and censors the press. In closing the court to a press member, respondent effectively closes it to the general public.

“The explicit, guaranteed rights to speak and to publish concerning what takes place at a trial would lose much meaning if access to observe the trial could, as it was here, be foreclosed arbitrarily. *** The right of access to places traditionally open to the public, as criminal trials have long been, may be seen as assured by the amalgam of the First Amendment guarantees of speech and press; and their affinity to the right of assembly is not without relevance. From the outset, the right of assembly was regarded not only as an independent right but also as a catalyst to augment the free exercise of the other First Amendment rights with which it was deliberately linked by the draftsmen. The right of peaceable assembly is a right cognate to those of free speech and free press and is equally fundamental. People assemble in public places not only to speak or to take action, but also to listen, observe, and learn; indeed, they may ‘assembl[e] for any lawful purpose’ Richmond Newspapers, Inc. v. Virginia, 448 U.S. 555, 576-577, 577–78, 100 S. Ct. 2814, 2827–28, 65 L. Ed. 2d 973 (1980) (internal citations omitted).

Respondent attacks complainant’s free exercise of religion and right of petition and remonstrance. Her May 6, 2024, demand letter expresses her intention to abrogate his free exercise of religion and his right to freely gather with others to enjoy the right of address, remonstrance and to “assemble together for their common good, to instruct their representatives, and to apply to those invested with the powers of government for redress of grievances,” Tenn const. art. 1, sect. 23.

The results sought are censorship under color of state office, closure of the court, each forbidden by law, and prohibition of assembly from which arise petitions for redress of grievance and remonstrance such as that in the Massengale case.

Respondent’s threats disregard the essential element of profit and gain, which omission she makes knowingly and intentionally, to bully complainant relator with erroneous arguments under color of law and under color of her office as the state’s attorney in judicial district 11. She knows how privilege operates, and so has actual or putative knowledge of its essential elements. That essential element is valuable consideration, which she admits is absent in relator’s doings.

All respondent’s evidence indicates relator works for free, in religious mercy; still, she makes threat of criminal prosecution lacking the essential element of valuable consideration. Such threats are in bad faith, knowingly and intentionally false, and oppressive of the rights of complainant and the people.

At the hearing in Judge Ables’ court, relator effectively tells the three ADAs present they have enough material to get an indictment, if such were possible. “Clearly the DAs have in this room right now all the evidence to bring indictment against me for the unlawful — the unapproved, the unauthorized — practice of law. They could do that. They’ve got paperwork to prove it. They’ve got me being here standing in front of you,” citing EXHIBIT No. 5, press report, p. 6.

Respondent knows any man, woman or person is free to file legal papers and argue in the courts, which are open, with justice mostly not for sale in Tennessee Petitioner sued Gov. Bill Lee in State of Tennessee ex rel David Jonathan Tulis v. Bill Lee, governor, et al, case No. E2021-00436-SC-R11-CV, representing the state of Tennessee in a petition for writ of mandamus against fraud and breach of T.C.A. § 68-5-104. Starting in Hamilton County chancery court, he litigated in his proper person before four courts 878 days before getting a “certiorari denied” order from the U.S. supreme court. (5) Up until Aug. 19, 2024, he had an appeal lodged in the 6th circuit court of appeals in Cincinnati in David Jonathan Tulis v. William Orange et al, case No. 23-5804, which case included suing Roger Page, chief justice at the time of relator’s false imprisonment and false arrest Nov. 6, 2021, in Franklin, Tenn., covering the secret Tennessee judicial conference.

In these and other cases he does his own law work, in persona propria, per right. A citizen’s filing of legal documents and appearing before judges are not unlicensed practice of law, despite respondent’s falsehoods intentionally uttered.

Respondent, in seeming malice, ignores T.C.A.§ 23-3-101(1). Chapter definitions. On p. 2 of her letter she says relator’s act of “drawing up and filing of” the Massengale remonstration and petition for a writ of certiorari “on behalf of another individual” is a crime, stating, “you have held yourself out repeatedly as ‘representing’ Tamela Grace Massengale, which is indicative of unauthorized practice of law.”

The attorney general’s office, in a form intended to bring reports of unlicensed practice of law, shows that payment for service is an essential element in a UPL action.

Since constitutional protections for right of redress, remonstrance and address in Tenn. const. art. 1, the bill of rights, apply to petitioner, the words used by relator to describe his gratis legal mercy next friend labor are not dispositive, and it is of no significance whether he says he is speaking “with” or “for” Mrs. Massengale given the strength of the underlying right of religion, assembly and redress.

“The power of the States to control the practice of law cannot be exercised so as to abrogate federally protected rights” id. Johnson at 490. (6)

Assistance is to help; aid; succor; lend countenance or encouragement to; participate in as an auxiliary. People v. Hayne, 83 Cal. Ill, 23 Fac. 1, 7 L.R.A.

Counsel is a term with broad, generally accepted meaning that includes lawyering and legal counsel and many other activities. Statutory and constitutional provisions are to be understood in their “plain and ordinary meaning. *** [W]here the statutory language is clear, we apply the plain and normal meaning of the words.” Commissioners of Powell-Clinch Util. Dist. v. Util. Mgmt. Rev. Bd., 427 S.W.3d 375, 381–82 (Tenn. Ct. App. 2013).

Credit repair agencies hire staff to give counsel. Ministers at North Shore Fellowship, where petitioner is member in good standing, give counsel from pulpits and in private sessions. Psychiatrists give counsel. Marriage counselors give wise words. Presidential and kingly advisers give counsel. (8) “Where there is no counsel, the people fall; But in the multitude of counselors there is safety.” Proverbs 11:14. “Then they said, ‘Come and let us devise plans against Jeremiah; for the law shall not perish from the priest, nor counsel from the wise, nor the word from the prophet. Come and let us attack him with the tongue, and let us not give heed to any of his words.’” Jeremiah 18:18.

Counsel is not a word exclusive to licensed business owner attorneys giving legal advice and drafting motions and briefs. The state and federal constitutions guarantee every defendant right to counsel of one’s choice.

It is not an offense nor a sin for a one-eyed man to help a blind man across the street. It’s not a crime for a man without medical training to give CPR to a man gagging over a piece of chicken. It is not an offense for a hair stylist at home to give a haircut to a shaggy nephew outside the scope of the Tennessee cosmetology act of 1986 at T.C.A. § 62-4-101. Legal filings, in and of themselves, are not under privilege, but per right of assembly and remonstrance. They become subject to privilege requirements if done for private profit and gain as part of an ongoing enterprise.

Argument

Complainant does not approach the board because of mistakes in judgment or a failure to perform duties. If it were possible for complainant to sue respondent under the ouster law, he would set forth with “reasonable certainty,” per sect. 113 that respondent Wamp is unfit for office. Removal, however, is in the general assembly’s authority alone. Ramsey v. Bd. of prof'l. Responsibility of Sup. Ct of Tenn. 771 S.W. 2d 116 (1989). The board’s authority is supervisory, administrative and ameliorative of respondent under her license with its strongest punishment being disbarment.

Evidence of official dereliction against four (4) constitutional guarantees is clear and convincing. Respondent’s actions are willful misconduct and reckless neglect of the law meriting correction up to suspension.

Miss Wamp’s motion to censor is a fraud the court, as if the court doesn’t know the difference between “the general public” and “a juror,” between “disruptive” news coverage under constitutional protection and “disruptive” acts or words during a court proceeding that interfere with running of a trial. It’s an intrinsic fraud on the court, coming from inside proceedings because it asks the court to share her offense at news coverage of the Rzeplinski case and to share respondent’s willingness to abrogate constitutional guarantees to prevent it.

Her motion to the tribunal violates rule 3.3 forbidding false statements of law, as to when juries are constituted, pretending the general public is the same as a jury pool.

Her threatening letter to relator is a fraud under color of office, misrepresenting the UPL statute by omitting reference to the valuable consideration in the definitions so that she may make threats and give appearance of having legal grounds in making them and demand a halt to relator’s Christian mercy ministry. She intends to abrogate free exercise of religion and relator’s rights of conscience by threat of criminal prosecution.

The premise of respondent’s ire about jury power also is faulty, based on a poor reading of law and the rights of jury members to vote their conscience. Miss Wamp decries jury nullification as an “unlawful idea. *** If jurors have been exposed to this unlawful concept it is a bell that cannot be unrung, and the state may have only one chance at trying his case.” She joins the censorship industrial complex run by the U.S. government under party spirit seeking to censor press content dubbed since 2020 “misinformation, “disinformation” and “malinformation,” as if ideas themselves could be illegal and dangerous, as if censorship is a project the DA dare undertake against widely known law and the rights of the people.

The jurisprudence on jury nullification holds no defendant has a right to jury nullification nor jury instructions recognizing it. (7)

Cases also indicate jury members’ voting their conscience is part of human nature and inescapable, a power of the people no court can outlaw..

While judges may not like juries’ ruling against law or against facts, the most they can do to limit jury nullification is to forbid lawyers from advocating it in proceedings.(10)

Regardless whether respondent’s beliefs about jury nullification are correct, her effort to bar the press and close the courts to prevent infection of wrong-think is audacious contumacy and oppression.

No court has authority to “suppress *** or censor events which transpire [in public] proceedings,” the court says, quoting State v. Montgomery 929 S.W.2d 409, 412, in denying respondent’s motion to censor coverage and close the courts.

Respondent’s analysis of the role of next friend is faulty because it doesn’t account for the absolute right of a defendant to have counsel of her choice. The next friend is not limited by judicial analyses on mental defects and such limits making it difficult for an prison inmate to get a third party to serve him legally.

If a criminal defendant chooses petitioner to speak with her or for her, there seems no proper way to deny her that right. But the court, using grounds similar to those of respondent, denies the Massengale remonstrance and petition for writ of certiorari drafted by relator.

Defendant’s role is initiatory, per right; next friends’ is responsive. Relator doesn’t have a right to be a next friend. The right under the constitution to name the next friend is entirely that of defendant. Relator respectfully submits the court has no authority to say, “[T]he Court finds that there is no basis for this Defendant to be appointed a next friend absent some showing that she is an infant or otherwise incompetent” (order p.2) (emphasis added).

When the defendant’s life and right are at stake, no authority exists for a court to “appoint” a next friend or disapprove of a defendant’s choice, that right belonging to the accused, who being one of the free people in state of Tennessee should be considered as a member of that body constituting the court and the state itself. Tenn. const. art. 1, sect. 1. (9)

Denial of Mrs. Massengale’s choice to counsel defeats her unalienable, inherent, God-given and constitutionally guaranteed right that relator defends in court..

Respondent in her motion to censor makes statements that verge on, even cross the line into, slander and defamation.

She implies petitioner is disposed to criminality. “Tulis also has had his own criminal cases in Hamilton County.” This statement is true, but the effect would be less harmful if she would point out her office justly dismissed the case, one arising from a false imprisonment and false arrest by a Hamilton County deputy. Respondent allegations of improper conduct with the foreman of the grand jury are made without stating the facts of the matter of why relator was having dealings with the foreman, Jimmy Anderson, which is relator’s right, a matter is outside the scope of this complaint.

Petitioner is not involved in the unlicensed practice of law which requires valuable compensation for the services rendered. Petitioner is not an attorney, does not practice law, does not have a law business, is not involved in the occupation, calling or trade of pleadings under law. Respondent has no evidence of it being otherwise, and does not directly state he is operating a business.

No evidence is presented that his activities as press member under Tenn. const. Art. 1 sect. 19 and promoter of judicial and legal reform is anything other than gratis in every court case and an enfleshment and living out of the grace the Lord Jesus Christ shown to all guilty sinners who repent.

He has stated many times his press and advocacy work are a diaconal service to the church at large, waiting tables, as it were, looking out for the widows, the alien and stranger, the poor and the oppressed. He is not for hire, nor is given valuable consideration for any act involving any legal filing or sharing of opinion. He makes no personal private profit except Christ’s reward for His servants. His acts are protected under the constitutionally guaranteed rights of assembly, remonstrance and religion.

Such mercy relationship is evidenced in Mrs. Massengale’s assignment affidavit regarding next friend on p. 11 of EXHIBIT No. 4, remonstrance & certiorari filing, Tamela Grace Massengale affidavit [o]n giving David Jonathan Tulis power of attorney, next-friend status.

Respondent threatens that his continuing religious free exercise is a crime she will abate under color of law, specifically a criminal prosecution as unlicensed practice of law. T.C.A. § 23-3-101 et seq.

The federally guaranteed rights petitioner intends to protect are that of the 1st amendment regarding speech, press, assembly and petition, the 14th amendment in its application of the bill of rights upon state of Tennessee, and the U.S. const. art. 4, sect. 4, guarantee as to Tennessee’s tripartite form of government with democratic processes. “The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government, and shall protect each of them against Invasion[.]”

The four Tennessee constitutional guarantees respondent commits herself to abrogate:

➤ “That all courts shall be open[.]” Art. 1 sect. 17

➤ “That the printing press shall be free to every person to examine the proceedings of the Legislature; or of any branch or officer of the government, and no law shall ever be made to restrain the right thereof. The free communication of thoughts and opinions, is one of the invaluable rights of man and every citizen may freely speak, write, and print on any subject, being responsible for the abuse of that liberty.” Art. 1, sect. 19

➤ “That all men have a natural and indefeasible right to worship Almighty God according to the dictates of their own conscience; *** that no human authority can, in any case whatever, control or interfere with the rights of conscience; and that no preference shall ever be given, by law, to any religious establishment or mode of worship.” Art. 1, sect. 3

➤ “That the citizens have a right, in a peaceable manner, to assemble together for their common good, to instruct their representatives, *** ” to confer, organize, gather, seek advice in mutual defense, in court or anywhere else. The people have a right to approach public servants in executive, legislative and judicial authority, to “instruct their representatives and to apply to those invested with the powers of government for redress of grievances, or other proper purposes, by address or remonstrance.” Tenn. const. art. 1, sect. 23

If these four areas of state constitutional law have any leaks, art. 11 § 16, gives a sweeping reminder of the subordinate role played by public servants and people in offices of trust. “Every thing in the bill of rights *** is excepted out of the General powers *** and shall remain forever inviolate,” it states.

The declaration of rights hereto prefixed is declared to be a part of the Constitution of this State, and shall never be violated on any pretense whatever. And to guard against transgression of the high powers we have delegated, we declare that every thing in the bill of rights contained, is excepted out of the General powers of government, and shall forever remain inviolate.

Tenn. const. art. 11, sect. 16.

In her motion to censor, respondent uses her public authority to abrogate constitutional provisions on courts and press. In her letter to complainant she uses threat to abrogate complainant’s rights of religion and remonstrance. Abrogating, or using fraud on the court to abrogate, constitutional rights is in violation of rules 3.3 on candor toward the tribunal and 8.4 on misconduct.

To say the jury pool is the same as the general public is false. To say next friend status exists only on death row and in service to lunatics or mental incompetents is false. To misrepresent jury nullification as an “unlawful concept” would mislead the court when the jurisprudence accepts the concept as inseparable from the existence of juries.. To nullify press rights because complainant is “obstructive and disruptive” to her political status respondent falsely equates to disruption of court proceedings. To demand closing the courts misrepresents well known press rights jurisprudence under 1st amendment and Tenn. const. Art. 1 sect. 19. Her grievance that complainant “attempted to influence jurors through his articles,” motion p. 5, is uttered in bad faith and malice because the general public and juror are not the same and the press is free. Complainant’s joining Mrs. Massengale in remonstrance and petition in the name of the state is not UPL, and to say so is bad faith and a deception against the court. Respondent violates repeatedly rules 3.3 and 8.4.

Her motion is an act of oppression, criminally indictable under § 39-16-403.

“We hold that the right of petition enshrined in Article 1, Section 23 of the Tennessee Constitution represents the unambiguous public policy of the State of Tennessee that citizens may petition their government.” Smith v. Bluecross Blueshield of Tennessee, No. E202201058COAR3CV, 2023 WL 3903385, at *8 (Tenn. Ct. App. June 9, 2023), appeal granted sub nom. Smith v. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Tennessee, No. E202201058SCR11CV, 2023 WL 8183880 (Tenn. Nov. 20, 2023).

Relator is not challenging the UPL statute. The law is clear that the practice of law is a privileged activity in business, in commerce, for hire, affecting the public interest, for profit and involving the selling of services, as id. Phillips makes clear. He consciously provides his reporting work and mercy ministry in a way to avoid offending this law. He strictly avoids any remuneration for mercy rendered.

The courts presume the constitutionality of statutes. “[E]very word contained in a statute has both meaning and purpose and should therefore be given its full effect if the General Assembly's obvious intention is not violated in doing so.” Doe v. Roe, 638 S.W.3d 614, 617–18 (Tenn. Ct. App. 2021) (emphasis added).

If a court determines that petitioner’s religious and petitionary free exercise as next friend to Mrs Massengale or others is forbidden by the unlicensed practice of law statute, he would believe himself obligated to challenge the law’s constitutionality.

Relief requested

Complainant respectfully demands the following:

Fair consideration of his complaint by disciplinary counsel and that it conduct an investigation and, based on the evidence and law herein, recommend “prosecution of formal charges before a hearing panel.” Sup.Ct.Rules, Rule 9, § 15.

That counsel discern substantial and material evidence in the complaint and thereafter demand process for the board to suspend respondent’s privilege to show the board’s recognition of the gravity of her actions against petitioner, the law and the public interest.

Respectfully submitted,

Footnotes

Roger Roots, The Conviction Factory; the Collapse of America’s Criminal Courts (Livingston, Mont.: Lysander Spooner University Press, 2014) 287pp

Mrs. Massengale in court attests: “I would like the court to recognize David Tulis as my next friend and counsel. By appointing him, I'm exercising my rights to appoint anyone of my choice for counsel. David is not an attorney. Nor has he ever claimed to be an attorney. David is just my next friend. To define next friend *** David is someone that I trust. David is someone that has knowledge of my case. David is someone that is much more knowledgeable in the law than I am. He is somebody that I look to for his opinion, somebody that I look to for support, and somebody that I trust. I also appoint David to speak for me on my behalf when needed. The court's recognition of David's status as my next friend must come first. If David is not recognized by this court as my next friend and I am denied this constitutional right and I feel that this court is not properly set and I will not be able to proceed.” “TRANSCRIPT: Judge threatens police victim ‘next friend’ as case defies illegal arrest warrants,” Davidtulis.substack.com, May 14, 2024, p. 4.. Link is incorporated by reference

https://davidtulis.substack.com/p/transcript-judge-threatens-police

In UPL at § 23-3-101, “valuable consideration” is an essential element of the offense:

“Law business" means the advising or counseling for valuable consideration of any person as to any secular law, the drawing or the procuring of or assisting in the drawing for valuable consideration of any paper, document or instrument affecting or relating to secular rights, the doing of any act for valuable consideration in a representative capacity, obtaining or tending to secure for any person any property or property rights whatsoever, or the soliciting of clients directly or indirectly to provide such services.

Inexplicably, Phillips v. Lewis is not on Westlaw and is nowhere to be found in digital form. Petitioner supplies the hard copy from a volume of Shannon’s code.

VAERS, the vaccine adverse event reporting system run by the U.S. government, says 1,517 jab death reports and 14,490 jab harm reports have been filed since Covid-19 shots began. That translates, given a URF (underreporting factor) of 100x, into 151,700 state deaths caused by law-breaking government policy, and 1.449 million injury events.

Justice Douglas, in concurring opinion in the Tennessee case id. Johnson, says laymen are more needed to help defendants and plaintiffs obtain justice.

But it is becoming abundantly clear that more and more of the effort in ferreting out the basis of claims and the agencies responsible for them and in preparing the almost endless paperwork for their prosecution is work for laymen. There are not enough lawyers to manage or supervise all of these affairs; and much of the basic work done requires no special legal talent. Yet there is a closed-shop philosophy in the legal profession that cuts down drastically active roles for laymen. ***

That traditional, closed-shop attitude is utterly out of place in the modern world1 where claims pile high and much of the work of tracing and pursuing them requires the patience and wisdom of a layman rather than the legal skills of a member of the bar. [emphasis added]

Today, 55 years after this Tennessee jailhouse lawyer case, the Internet has brought rich abundance of legal means and aids into the hands of pro ses, next friends and others seeking to render aid and mercy to distressed poor people and others in exercise of their right to counsel.

Although it is conceivable that a jury would decline to do so, such a failure to follow the law is nothing but a windfall to the defendant because he does not enjoy a personal right to jury nullification.1 This Court has declined to find that jury nullification is a personal right of the defendant. See Jerry Lee Craigmire v. State, No. 03C01–9710–CR–0040, 1999 WL 508445, at *12 (Tenn.Crim.App., at Knoxville, Jul. 20, 1999), perm app. denied (Tenn, Nov. 22, 1999). Our state supreme court has said that jury nullification is neither a personal right of the accused nor of the jury itself, although juries sometimes do nullify applicable law. Wright v. State, 217 Tenn. 85, 394 S.W.2d 883, 885 (Tenn.1965).2

State v. St. Clair, No. M2012-00578-CCA-R3CD, 2013 WL 1611206, at *6 (Tenn. Crim. App. Apr. 16, 2013) (emphasis added)

“Privy counsellors are made by the king's nomination, without either patent or grant; and, on taking the necessary oaths, they become immediately privy counsellors during the life of the king that chooses them, but subject to removal at his discretion.” William Blackstone, Commentaries on the laws of England, introduction. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/30802/30802-h/30802-h.htm

The Tennessee bill of rights, art. 1, sect 1, says the following:

That all power is inherent in the people, and all free governments are founded on their authority, and instituted for their peace, safety, and happiness; for the advancement of those ends they have at all times, an unalienable and indefeasible right to alter, reform, or abolish the government in such manner as they may think proper.

The applicable rule is that, although jurors possess the raw power to set an accused free for any reason or for no reason, their duty is to apply the law as given to them by the court. *** Accordingly, while jurors may choose to flex their muscles, ignoring both law and evidence in a gadarene rush to acquit a criminal defendant, neither the court nor counsel should encourage jurors to exercise this power. *** A trial judge, therefore, may block defense attorneys' attempts to serenade a jury with the siren song of nullification *** ; and, indeed, may instruct the jury on the dimensions of their duty to the exclusion of jury nullification.

United States v. Sepulveda, 15 F.3d 1161, 1189–90 (1st Cir. 1993) (internal citations omitted) (emphases added)