Angry that U.S. judge is asked to ‘stay’ anti-fraud lawsuit over financial responsibility

AG's office intends to deny relief of any kind in corporate capitalism op that holds captive Tennessee department of revenue

Defendants revenue commissioner David Gerregano and his department have no authority to hold hearings for financial responsibility.

Under T.C.A.§ § 55-12-103. Administration; hearings; appeal and review, the department of safety (“DOSHS” or “safety”) is charged with enforcement of the law and holding hearings in contested cases prior to any revocation of license or tag.

[This post is a ferocious and demolitive reply as to why the federal judge in charge, Waverly Crenshaw, should not put this case “on hold” but bring relief to me and to 1 million Tennesseans oppressed by rogue government.]

Thus, contrary to defendants’ abstention motion [bid to force U.S. district court judge to halt proceedings in Nashville in the middle Tennessee district], the Younger doctrine does not apply because their program flagrantly and unconstitutionally denies due process rights to a hearing, an exception to Younger.

Defendants say abstention is just because proceedings are occurring inside the department. Two controversies, each with its own parties and facts, are in the court’s consideration. This case in the particulars seeks to prevent tag revocation of a Toyota RAV4, registered to wife Jeannette M. Tulis, trustee. The “ongoing” “underlying state action” and “ongoing civil enforcement proceedings” (as defendant calls them) (Doc. 5, PageID ## 116, 118, 120, 121) are over a car registered in plaintiff’s name.

Two sets of facts. Two citizens. One administrative case on one car. One civil enforcement action threatened upon another.

‘Ongoing civil enforcement’?

The case in agency is not an “ongoing civil enforcement proceeding” because state enforcement proceedings end with revocation and mailing of notice. In the ongoing Honda Odyssey minivan case (“Honda Odyssey”), plaintiff is the moving party suing for restoration of a tag.

The controversy over the Toyota RAV4 (“Toyota RAV4”) to date is pre-revocation. Honda Odyssey is pre-judicial.

Plaintiff exposes an extraordinary circumstance in state government, a rogue program fraudulently imposing criminal prosecutions on tens of thousands of innocent Tennesseans and involving every law enforcement agency statewide in harassment, abuse of process, official misconduct and criminal oppression. Relief instanter cannot be secured apart from intervention of this court.

Background

Not only is plaintiff denied due process, defendants are acting in bad faith because they refuse to yield to the plain and unambiguous meaning of the law that shows only insurance company-certified SR-22 motor vehicle liability insurance policies are the subject of the Tennessee financial responsibility law and its insurance verification program under the Part 2—Insurance Verification Program (“James Lee Atwood JR. Law”) (“Atwood”).

Defendants refer to the Honda Odyssey “underlying proceeding” as invoking Younger abstention. Department of revenue (“DOR” or “revenue”) cannot rule in plaintiff’s favor because the department lacks authority to hold hearings.. The law says revenue cannot restore a tag, revoked under TFRL by safety, without a letter from safety. T.C.A. § 55-12-130.

Quick take ——————————

— Guano seeks cover behind ‘Younger’ doctrine in which federal courts defer to states’ rights

— I demand intervention because no state proceedings are in progress that can be interrupted

— Revenue can’t hold hearings under TFRL, so my admin case is void

The commissioner claims that Honda Odyssey and Toyota RAV4 are “the same.” He alleges they are judicial, that both are in process together, giving himself leave to continue irreparable harm upon plaintiff and 6.34 million members of the registered motoring public serving not the interest of the state and its people, but the interest of the insurance industry and its state-employed boosters apart from law.

The Part 1—Tennessee financial responsibility law of 1977 (“TFRL”) and Part 2 Atwood say certified motor vehicle liability policies per § 55-12-102, definitions, are proof of financial responsibility. Defendants impose on the general public a condition precedent to members’ use of the people’s roads under color of claim that its members have a duty. The extortion program commands members of the public to purchase noncertified insurance policies under TFRL when certified motor vehicle liability policies are the enforcement mechanism in the law.

Motor vehicle liability policies are certified per Tenn. Code Ann. § 55-12-102, -119, -120, -121, -123, -125, -126, -133, -136, -139, -210 and -212. They are sold by participating insurance companies with SR-22 certificates to people who are required to show proof of financial responsibility (“POFR”), these being among a limited group: Person (1) with unsatisfied judgment based on a motor vehicle accident, § 55-12-114, (2) have a motor vehicle-related criminal conviction, § 55-12-114, (3) are under suspension for “willfully fail[ing], refus[ing] or neglect[ing] to make or have filed an accident report” § 55-12-104, or (4) are under suspension by commissioner of safety for violation in other vehicle-related matter. These parties, unlike plaintiff, are subject to claim under TFRL. These individuals under condition of POFR or proof of financial security retain the driving privilege for exercise of rights and livelihood, despite their irresponsibility, carelessness, acts of neglect or high risk.

Only ‘certified’ policies focus of TFRL

Noncertified auto policies are a matter of indifference in the law. The TFRL and Atwood concern themselves with high-risk drivers with a record of irresponsibility and with certified motor vehicle liability policies that cement the state-driver relationship under seal for the duration of the privilege suspension. In sect. 139, the officer is to use EIVS to verify a certified policy. Further,

If a person has a certificate of compliance with the Tennessee Financial Responsibility Law of 1977, compiled in chapter 12 of this title, issued by the commissioner of safety, a copy of the certificate shall be included in the report.

Tenn. Code Ann. § 55-10-108 (emphasis added)

Knowing such persons pose a risk to the traveling and shipping public, state of Tennessee consents to use of the public road by such persons if it certifies they have a minimum liability policy described in the law, such certificates given in the form of SR-22 and accepted by department of safety and its financial responsibility division. Fact that liability policy was on file and approved by Commissioner of Insurance and Banking did not make policy a “certified policy” under financial responsibility statute. T.C.A. §§ 56-603, 59-1201 to 59-1240. McManus v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 1971, 463 S.W.2d 702, 225 Tenn. 106 (emphasis added)

Court cases indicate Tennessee is an after-accident voluntary insurance state, not an “insurance-is-mandatory-on-100-percent-of-registrants-100-percent-of-time” state, despite amendment via sect. 139 in 2001 and Atwood in 2015.

I demand program be ‘decertified’

Plaintiff in administrative proceedings in agency challenges revocation of his tag and the operation of the electronic insurance verification system (“EIVS”) as legislation by the executive branch. He has grounds to prosecute his claims administratively, having let an ordinary non-certified insurance policy lapse on the Honda Odyssey, focus of litigation since July 26, 2023. In the cause he defends the law as constitutional, moral and serving the public’s interest. He demands restoration of his tag and a decertification, pursuant to Tenn. Code Ann. § 55-12-212, of the facially unconstitutional revocation program.

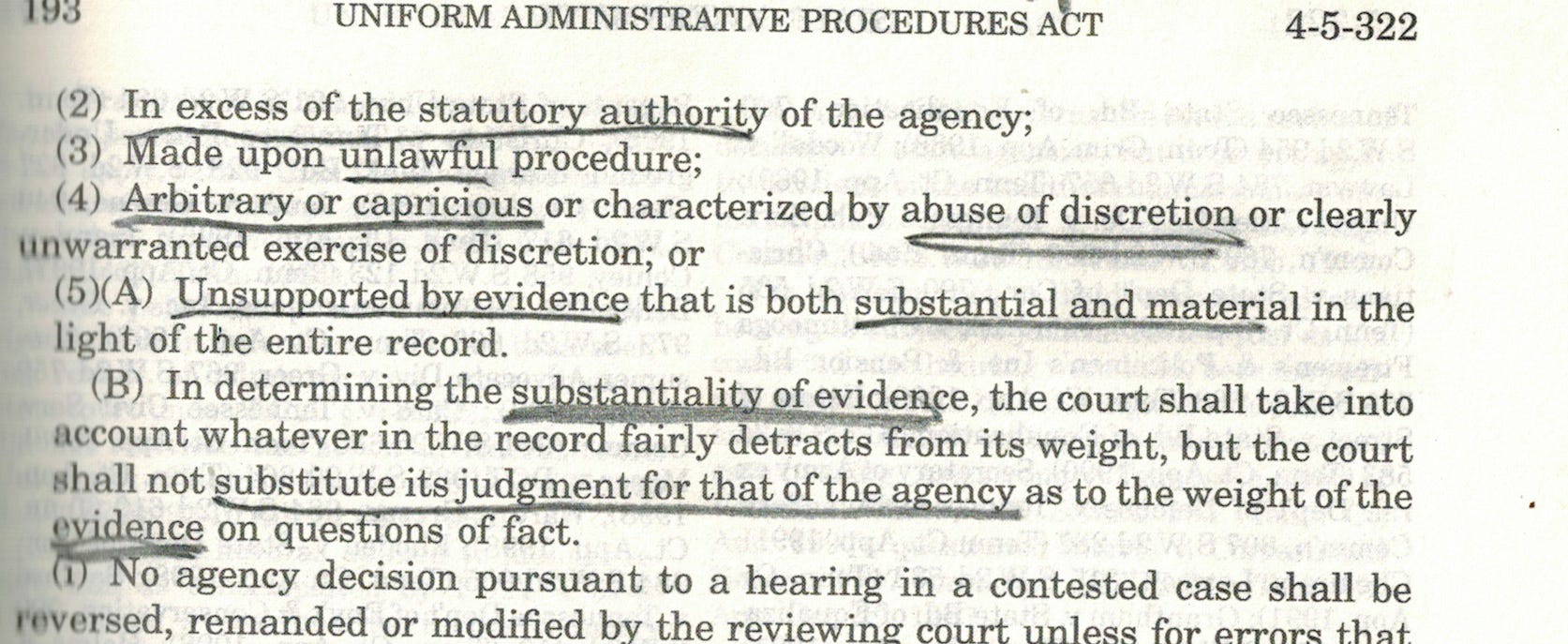

He challenges defendant conduct on TFRL as “flagrantly and patently unconstitutional” Huffman v. Pursue, Ltd., 420 U.S. 592, 592, 95 S. Ct. 1200, 1202, 43 L. Ed. 2d 482 (1975). He’s not asking the court to “exercise any such power of prior approval or veto over the legislative process.” Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37, 53, 91 S. Ct. 746, 755, 27 L. Ed. 2d 669 (1971). He’s not asking it to intervene in a case filed for judicial review. The agency case is judicial in form. Administrative hearing officer Brad Buchanan sits in the place of the commissioner, Mr. Gerregano. Each man is in office as administrator. The case is being administered internally until it enters adjudication by petition for judicial review. T.C.A. § 4-5-322, if indeed a void case are appealable.

Four cases cited by defendant (Doc. 5-1 PageID # 117) pertain to attorney and judge discipline, considered to be “judicial in nature” and “as such *** of a character to warrant federal-court deference” Middlesex Cnty. Ethics Comm. v. Garden State Bar Ass’n, 457 U.S. 423, 424, 102 S. Ct. 2515, 2517, 73 L. Ed. 2d 116 (1982). Cited cases are not like this cause, where state interest in right operation of law is extravagantly and injuriously denied by the state itsel, with plaintiff denied right of appeal.

In Honda Odyssey plaintiff is prosecutor. The department is respondent, its enforcement activity having ceased with notice of revocation. Proceedings may become judicial if Cmsr. Gerregano and DOR don’t make reform within the department under the commissioner’s “[coming] to himself,” as does the Prodigal Son in the Lord’s parable, Luke 15:11 ff. For now, no adjudication fitting for Younger deference appears in progress.

Defendant claim: ‘Same issue’ = same case

The commissioner alleges the Younger doctrine requires the court to stay the case because Honda Odyssey is a “state judicial proceedings,” citing O’Neill v. Coughlan, 511 F.3d 638, 643 (6th Cir. 2008), citing Younger, 401 U.S. at 40–41 (Doc. 5-1, ID# 117).

Defendant Gerregano notes the abstention principle is based on three criteria, “(1) the underlying proceedings constitute ongoing state judicial proceedings; (2) the proceedings implicate important state interests; and (3) there is an adequate opportunity to raise constitutional challenges in the course of the underlying proceedings,” p. 4. “The RAV4 notice constitutes an ongoing judicial proceeding. The Department has initiated the action by administering the EIVP and notifying Plaintiff of non-compliance. Investigations without formal government action may constitute ongoing state proceedings for purposes of Younger analysis” (Doc. 5-1, Page ID# 117).

He says letting the suit proceed “would interfere with the ongoing state proceeding regarding the registration of Plaintiff’s Odyssey” and suggests “[p]laintiff’s claims are not based on any differences between the registrations of the two vehicles.” He argues that if the court shuts down the program on behalf of the RAV4, it would resolve Honda Odyssey, too, and thus “interfere” with a “judicial proceeding”: “Thus, a ruling by this Court as to Plaintiff’s claims regarding the RAV4 registration would also address the same issues in the underlying state proceeding regarding the Odyssey registration[.]” (Doc. 5-1, Page ID# 119)

He says the state “has a highly legitimate governmental interest in maintaining, protecting, and regulating the public safety,” and identifies the challenged program as serving the state, protectible under Justice Black’s reference to the “the legitimate activities of the States” not to be “unduly [interfered] with” by the national government’s protecting federal rights and federal interests, Id. Younger at 44 (Doc. 5-1, Page ID## 119, 120).

To say Toyota RAV4 is “the same” as Honda Odyssey means, effectively, that no matter how many plaintiff autos fall victim to defendant policy, he cannot appeal for federal intervention because all cars are revoked under the same program, and thus each is inseparable from Honda Odyssey under Younger.

Because the system is automated, all cases connected with any one are indistinguishable. This claim is unreasonable. Two cars, two owners, one contested case in process, hearing denied on second car. A program’s being systematic and treating everybody alike with no human intervention is no defense for state and federal crimes under color of office.

‘Lack of an adequate state forum’ exception

Lack of a forum is an exception to Younger. The supreme court in Gibson v. Berryhill, 411 U.S. 564, 93 S. Ct. 1689, 36 L. Ed. 2d 488 (1973) determines that an optometry board comprised of members “with substantial pecuniary interest in legal proceedings should not adjudicate such disputes,” thus depriving complainant of right to due process.

Normally when a State has instituted administrative proceedings against an individual who then seeks an injunction in federal court, the exhaustion doctrine would require the court to delay action until the administrative phase of the state proceedings is terminated, at least where coverage or liability is contested and administrative expertise, discretion, or factfinding is involved. But this Court has expressly held in recent years that state administrative remedies need not be exhausted where the federal court plaintiff states an otherwise good cause of action under 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

Gibson v. Berryhill, 411 U.S. 564, 574, 93 S. Ct. 1689, 1695–96, 36 L. Ed. 2d 488 (1973)

Honda Odyssey is entangled in administrative contested case in defendant department without authority for a TFRL hearing. Safety handles financial responsibility law hearings at Tenn. Code Ann. § 55-12-103. The Gerregano brief makes no claim otherwise except to dispute plaintiff’s claim that the uniform administrative procedures act (“UAPA”) excludes its application to the department, Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-106(f). Defendant commissioner admits no authority under statute. See complaint (Doc. 1, Page ID ## 9, 10, ¶¶ 31-35).

Tennessee law respects due process rights in that Tenn. Code Ann. § 55-12-103 gives hearings under TFRL in safety. Revenue has no authority for a hearing. Under sound rationale, revenue exercises limited tax authority in the motor vehicle Title 55. The registration tag is proof of tax paid. T.C.A. § 55-4-101(a)(2). Revenue is given no authority to initiate acts pertaining to TFRL, administered by department of safety.

DOR acts responsively under notice from the safety commissioner. DOR has a subservient or step-and-fetch-it role. Its authority to revoke tags under T.C.A. § 55-12-210 is upon parties who let lapse an SR-22 motor vehicle liability policy when required under chapter 12 by the commissioner of safety. Revocations against this small group — fewer than 3,000 people, based on DOR information — is nondiscretionary, ministerial and administrative. No hearings are held.

Absence of a lawful state forum for petitioner to make his case is an exception that should prompt denial of the commissioner’s motion of abstention. Id. Younger at 53, 54.

Honda Odyssey is not in adjudication. Adjudication would begin in appeal to chancery court Davidson County, pursuant to the UAPA at Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-322. The controversy is being administered, with plaintiff the moving party. Camille Cline, staff attorney, in an affidavit states “[t]he administrative proceeding is ongoing” (Doc. 5-2, PageID # 123). Nothing criminal is in view in Honda Odyssey, Docket no. 23-004, criminal proceedings being the concern in the original Younger.

In void case, I am ‘consultant’

At Honda Odyssey’s Nov. 22, 2024, hearing, plaintiff tells DOR that while the proceedings are void, the evidence in “the record is going to need to be considered by somebody,” indicating petitioner intentions to have DOR “get legal.”

By belligerently making his claims in person internally in the department, the petitioner intends to force decertification of the program per T.C.A. § 55-12-212. Program certification and implementation. Effectively, he is adviser, consultant or counsel to defendant, such office abdicated by offices of attorney general and comptroller of the treasury.

Defendants legislate “mandatory insurance for all” apart from clear, well-known law. In New Orleans Pub. Serv., Inc. v. Council of City of New Orleans, 491 U.S. 350, 371, 109 S. Ct. 2506, 2520, 105 L. Ed. 2d 298 (1989), a ratemaking case, respondents make the Younger argument similar to that of defendants that proceedings are “an uninterruptible whole” and judicial. The high court says “the Council’s proceedings here were plainly legislative.” A federal court, it says, should not abstain when the ongoing state proceeding involves a state court engaged in an essentially legislative act. In instant case, an executive branch department legislates unwarranted police power infrastructure outside of law — and holds “hearings.” DOR’s simulacrum of adjudication is unfit for Younger protection for ongoing judicial proceedings.

Argument

Instant case is without precedent in Tennessee. Plaintiff challenges a rogue program under color of law, established by defendants Jan. 1, 2017, in the EIVS system going live upon the general public. Plaintiff is not demanding federal interference of a “legitimate [activity]” of the state. Id. Younger at 44. State of Tennessee does not have “legitimate interests” in defrauding the poor of enjoyment of interstate commerce rights.

Plaintiff’s case is outside Younger claims because he challenges not a criminal prosecution, nor a judicial proceeding nor a law, but an arbitrary and capricious program. He is not asking the court to “survey the statute books and pass judgment on laws before the courts are called upon to enforce them” Id. Younger at 52. The Younger court grants the “bad faith” exception when a law is exhaustively misguided and unconstitutional. Here, defendants brazenly abrogate a valid and constitutional law. Commissioner’s personal actions under color of law cause harm to plaintiff and, more importantly, to the law itself and public confidence in law and state institutions.

Defendant suggests that a future RAV4 contested case is “the same” as Hond Odyssey whistleblowing DOR abuse 16 months. He warns that a grant of relief in this case without Younger will unjustly interfere with administration of Honda Odyssey, with its Nov. 22, 2024, final hearing and a 60-day deadline for a ruling to issue, no later than Jan. 21, 2025.

“Plaintiff’s claims are not based on any difference between the registrations of the two vehicles,” defendant states. “Instead, Plaintiff claims that the commissioner has exceeded his statutory authority and violated Plaintiff’s constitutional rights and otherwise harmed Plaintiff by administering the EIVP as to all registrants instead of only those who have been in a car accident” (Doc. 5-1, Page ID# 119) (emphasis added). “Plaintiff challenged the suspension, and the resulting administrative proceeding and judicial review have already provided – and will continue to provide — him” with due process (Doc. 5-1, Page ID# 118). But he errs. No judicial review “[has] already been provided” as to threatened Toyota RAV4 tag.

Defendant’s argument incorporating Toyota RAV4 into Honda Odyssey is unreasonable defendant prophesying. (1) No file or record exists in a future RAV4 contested case. (2) Commissioner has no grounds to say the process for future judicial review in Honda Odyssey “have already provided – and will continue to provide – him” with due process. (3) Can Joe be denied a hearing in federal court regarding one car just because Sue has a case anticipated in a state agency for another? Seemingly, to ask the question is to answer it. No. It is plain error and misleading the court to say there is not “any difference between the registrations.”

Commissioner’s Younger defense is that EIVS is automated, and no administrative proceeding is distinguishable from another. A contested case for one motor vehicle is the same as that for a second, third or fourth car that may face revocation. Identical defendant process involving one or more motor vehicles means no prospect for federal relief. Honda Odyssey has its own facts; Toyota RAV4 has separate facts – different registrant names, different tag numbers, different VINS, colors, models.

This case does not ask the court to pass judgment on a statute. It is not asked to find that the TFRL “might be flagrantly and patently violative of express constitutional prohibitions in every clause, sentence and paragraph, and in whatever manner and against whomever an effort might be made to apply it” Id. Younger at 53, 54. Plaintiff is defending the statute. He demands its unambiguous provisions be obeyed, and thus obtain relief. What is oppressive in Tennessee is “every clause, sentence and paragraph” of defendants’ protocols, policies, administrative case pleadings, its customs and usages under color of TFRL.

In this case extraordinary circumstances are present to justify federal injunctive relief on proper motion, and a denial of defendant’s motion to stay.

Department of revenue cannot rule in plaintiff’s favor; it does not have authority to hear the case. Petitioner cannot receive relief or equity from revenue. If he and Mrs. Tulis file for a contested case in revenue on Toyota RAV4, it would be in a department that cannot hold a hearing, and plaintiff has no standing to file a contested case petition in safety under T.C.A. § 55-12-103. He is denied right to a hearing. Overlooking the maxim that the law does not require a futile thing, he sends on Oct. 9, 2024, a certified demand letter to DOR demanding a hearing for Toyota RAV4 before revocation, without reply.

Defendants are continually violating plaintiff’s and the citizenry’s federally protected rights. They abrogate due process by denying a hearing before revocation. They burden plaintiff into an administrative proceeding not authorized by the Tennessee financial responsibility law. The only equity for plaintiff is in federal court. Plaintiff asks the abstention motion be denied.

David runs a personal nonprofit fighting and mercy ministry. He thanks you for checks sent directly to c/o 10520 Brickhill Lane, Soddy-Daisy, TN 37379. Also, in GiveSendGo

"""The commissioner claims that Honda Odyssey and Toyota RAV4 are “the same.” He alleges they are judicial, """"

Statutory courts have NO JUDICIAL AUTHORITY.

One relevant case is "Ex parte Young" (209 U.S. 123, 1908), which highlights the distinction between constitutional and statutory authority in certain contexts. However, the idea that "statutory courts lack judicial authority" is often derived from interpretations of cases involving jurisdictional limits, like "Mookini v. United States" (303 U.S. 201, 1938), which distinguishes between constitutional courts (Article III) and legislative courts.

It is important to note that there ARE NO ARTICLE THREE COURTS IN EXISTENCE. They are ALL legislative courts.